One day after the deadly July 5 riots in Urumqi and other parts of Xinjiang, I was observing how unusually candid Chinese authorities were about the incident, allowing the outside world to see more of rural violence than was usually the case. As I wrote back then, Chinese media and local authorities allowed the release of extremely graphic pictures not only of the clashes themselves, but also of their victims. Why, I asked then, was China allowing this, given that doing so would undermine the image of stability it has long sought to broadcast abroad?

One day after the deadly July 5 riots in Urumqi and other parts of Xinjiang, I was observing how unusually candid Chinese authorities were about the incident, allowing the outside world to see more of rural violence than was usually the case. As I wrote back then, Chinese media and local authorities allowed the release of extremely graphic pictures not only of the clashes themselves, but also of their victims. Why, I asked then, was China allowing this, given that doing so would undermine the image of stability it has long sought to broadcast abroad?The answer, it turns out, is all in how it’s spun, a subject that Chinese writers Chen Guidi and Wu Chuntao touch upon in their highly readable Will the Boat Sink the Water: The Life of China’s Peasants. Through a number of case studies (mostly in Anhui Province), Chen and Wu demonstrate how individuals at the bottom of China’s so-called socialist society are mistreated, overtaxed and abused, with little recourse for redress, let alone compensation. In case after case, we see peasants struggling to bring justice to their villages and townships, first turning to local (and often corrupt) officials, only to be turned back or beaten by thugs hired by the authorities. On some occasions, peasants manage to bring the case to the county level — and sometimes even to Beijing — only to see their hopes dashed as reports and recommendations go down the chain of command, and requests for investigation trickle down to those who were responsible for the abuse in the first place, whereupon peasants are punished, beaten, arrested, and sometimes murdered.

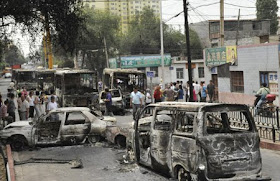

When whole villages say enough is enough and mobilize, riot police is called in, resulting in mass arrests and more violence. It is here, I think, when tensions have reached a boiling point, when whole villages rise up, that lies the key to the Xinjiang riots and why the government allowed the story to come out. In the cases discussed in Chen and Wu’s book, the “official” story — that is, the one sanctioned by the authorities and reported by state-controlled media — focuses on the violence without providing any of the background, or any of the accumulation of top-down injustice that led to conflict. By spinning “riots” as instantaneous acts of violence threatening social stability rather than an ultimate act of desperation, it is easy for the Chinese government to depict the “rioters” as “extremists” and “terrorists.” In many of the cases exposed in the book, the victims often end up portrayed as the aggressors, while the heavy-handed police response — often unwarranted and disproportionate — is ignored.

The same applies to the July 5 riots. While we saw and read much about the “spontaneous” violence, we were provided with little information, if any, about the root cause of the problem, which was likely the accumulation, over months (if not years), of grievances by the oppressed party (Uighurs). Based on the precedents laid out in Chen and Wu’s book, we can safely assume that Uighur leaders went to the authorities to try to resolve matters and apprise cadres of whatever injustice they were suffering. We can assume as well that their pleas were ignored. It is quite likely that some of them were arrested or beaten; in fact, their ethnicity as Uighurs and minority status probably made it easier for Han authorities to mistreat them and to ignore their pleas.

The riots were not orchestrated from abroad, nor, unlike what Beijing claims, did World Uighur Congress Rebeya Kadeer sanction them. This wasn’t terrorism either. Far more likely, it was a situation that came to a boil after calls for justice were ignored again and again. This knowledge allows us to question the veracity of official Chinese claims that the majority of the 200 or so dead were Han killed at the hands of Uighur, and to be critical about the circumstances under which they lost their lives: Were they innocent bystanders, or were they, too, armed and involved in the violence? Were they the victims, or the aggressors?

Far more than just exposing the widening gap between rich and poor in China, or the inefficiency that is inherent in a system of government in which the ratio of official to commoner is 1:67 (5,430,000 people on government payroll in 1989), with no less than five levels of government, Chen and Wu’s work of investigative journalism sheds precious light onto Chinese media reporting on unrest in rural areas and how even apparent openness, such as we saw during the Xinjiang riots, in fact masks all the important points.

(One odd thing about the book is that Chen and Wu used their real names for the publication of Zhongguo Nongmin Diaocha (The Life of China’s Peasants), which, as expected, had deleterious consequences for their careers (they are husband and wife). Soon after their book was banned, bricks were thrown at their house, and police would not intervene. They were sued, denounced on TV, and Chen was forced to resign from his job. Given everything they had seen, one wonders how they could have imagined that their book would be welcomed by the Chinese government, or that they would not be harassed for publishing it.)

many chinese seem quick to react against perceived threats to china with violence. chinese nationalism seems scary to me. if people in china were allowed to have honest public debates in academia and the media over issues like Taiwan and Tibet, would this change attitudes and help to curb nationalism...? nationalism seems to have a nice breeding ground in the CCP polity that co-opts it for its won purposes... but how to expose it for the empty shell that it really is? thanks for your blog... it always raises too many big questions for me :)

ReplyDelete