This book [Democracy in Peril: Taiwan’s Struggle for Survival from Chen Shui-bian to Ma Ying-jeou] is highly timely: it covers the last few months of Chen Shui-bian’s DPP administration and the first year of Ma Ying-jeou’s KMT government. It presents razor-sharp insights into the events that unfolded during the past two years, and — as stated in the introduction — “…very much reflects the realities, struggles and challenges that are specific to that historical period in the nation’s history.”

[…] The intention of the book is to contribute to the readers’ understanding of the great debate that was — and is — going on in Taiwan during the transition from the Chen administration (when the focus was on the struggle for international survival) to the present Ma administration, marked by rising fears of Chinese encroachment as the ruling KMT initiates a series of “peace” initiatives with Beijing.

Readers can access the full review, as well as issue No. 125 of Taiwan Communiqué here.

Sunday, August 30, 2009

Taiwan Communiqué’s Gerrit van der Wees reviews my book

Wednesday, August 26, 2009

Let’s bring things back to the center

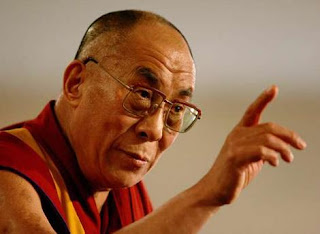

The Central News Agency reported today that Tibetan spiritual leader the Dalai Lama will be visiting southern Taiwan next week to bring comfort to the victims of Typhoon Morakot. According to the news agency, the Dalai Lama is expected to arrive on Monday and remain in Taiwan until Sept. 4, but there was no news yet as to whether he would meet Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九).

The Central News Agency reported today that Tibetan spiritual leader the Dalai Lama will be visiting southern Taiwan next week to bring comfort to the victims of Typhoon Morakot. According to the news agency, the Dalai Lama is expected to arrive on Monday and remain in Taiwan until Sept. 4, but there was no news yet as to whether he would meet Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九).Should this come to pass (after all, the Dalai Lama needs a visa to be allowed to enter the country, which the Ma administration denied him in December last year, claiming the timing was not right), this would be good news for two reasons:

First, very few people alive today could bring as much spiritual comfort to the victims of Morakot as the Dalai Lama. Southern Taiwanese would undoubtedly be uplifted by the presence of a man who stands for universal values of humanity and compassion. In fact, he would bring to the people what their president, who remained aloof and distant, failed miserably to provide during those extraordinarily trying times. Taiwan has long been a friend of the Dalai Lama and Tibetans; this would be an occasion for the spiritual leader to reciprocate.

Secondly, by granting the Dalai Lama permission to visit, Taiwanese authorities would demonstrate that they remain willing to stand up to Beijing, as there is no doubt China would be “angered” by the presence of the Dalai Lama on Taiwanese soil. The Ma administration’s willingness to risk that could very well be the result of widespread popular dissatisfaction at its handling of Morakot. In fact, approval levels for Ma and his Cabinet have tanked to such an extent that this time around they may be in no position to turn the Dalai Lama down (it would be interesting to see who, in the “green” local governments, initiated the idea of the visit; as I argued in an article back in December, anyone who wanted to cause Ma headaches should pressure Taipei to allow such a visit). Furthermore, allowing the visit could help the Ma administration score some political points — which it is desperate for nowadays.

Externalities

Years ago, when I was doing graduate studies in armed conflict, I remember a professor mentioning that political conflict will sometimes be dramatically influenced by external factors, external in that they are unexpected and not part of the known variables (e.g., leadership, balance of power, allies, etc). One such external factor was nature. Here’s the implication for conflict in the Taiwan Strait:

Since Ma came into office in May last year, the direction of the protracted political conflict in the Taiwan Strait changed substantially and, according to many, it shifted in Beijing’s favor, in that cultural and economic integration were bringing about inevitable political adjustments (i.e., closer Sino-Taiwanese ties, distancing from Tokyo, etc). At the height of this rapprochement, Taipei did everything in its power to keep things on track — even, as we saw, denying a visit by the Dalai Lama because it would risk creating problems with Beijing.

Less than a year later, however, the blow that Typhoon Morakot has dealt the Ma administration — in that it no longer is in a position to ignore popular discontent as it forges ahead in its cross-strait policies — is forcing the Ma Cabinet to pay more attention to domestic politics, from which the Dalai Lama visit cannot be dissociated. In other words, the domestic cost of denying a visit by the Dalai Lama would be far greater now than it was back in November. An offshoot of this is that Taipei is being forced to make a policy decision that it knows will anger Beijing, which accuses the Dalai Lama of being a “splittist” and seeking to “break China apart.” The ramification of this visit is that we will likely see the first crisis in cross-strait relations since the Beijing-friendly Ma came into office: expect, once the Dalai Lama has arrived in Taiwan, to see accusations across the strait of Ma siding with a “splittist,” or of breaking his promise to abide by the “one China” principle. Attendant to this will be a hardening of positions, with both sides moving toward the political center — in other words, toward the “status quo” of old.

For Taiwanese independence, this is an immensely positive development, despite the great human cost that made this possible.

Monday, August 24, 2009

China should not be ‘lectured’

The Toronto Star had an excellent — and moving — piece by Iain Marlow about Huseyin Celil, the Uighur human rights activist of Canadian citizenship who has been rotting (almost literally) in jail for three years because of his alleged “splittist” activities.

The Toronto Star had an excellent — and moving — piece by Iain Marlow about Huseyin Celil, the Uighur human rights activist of Canadian citizenship who has been rotting (almost literally) in jail for three years because of his alleged “splittist” activities.The story puts officials at the Department of Foreign Affairs and staff at the embassy in Beijing to the task for their “amateur” handling of the case, quoting Charles Burton, a specialist on Sino-Canada relations and former in-house counselor at the Canadian embassy in Beijing, as saying that Canada’s foreign service remains intellectually ill-equipped to engage in the types of diplomacy that might have freed Celil: “The people that we have working in China don’t have, first of all, the linguistic competence to be able to engage in diplomacy with the Chinese elements that are holding Mr. Celil.”

“They don’t have the cross-cultural communication skills to know how to approach the agencies that are responsible for his incarceration, to try and come up with some means to negotiate a satisfactory resolution,” Burton says.

While all this may be true (and my experience in the Canadian government supports that view), Marlow argues that ultimately it was the “ideological federal politicians in Canada, whose public statements may have crippled diplomats’ efforts” that are to blame for Ottawa’s failure to secure Mr. Celil’s release. The author also quotes Errol Mendes, a law professor at the University of Ottawa, on Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s “damaging” statements regarding the affair: “What I’ve learned, after going to China almost every year for the past 15 years, is that the Chinese do not take kindly to people lecturing them. And the thing they need, more than anything else, is [help] trying to figure out a way of resolving disputes without losing face.”

What Mendes seems to be saying is that if Canadian diplomats had been willing to compromise on human rights and find a way to secure Celil’s release without Beijing losing face, the outcome could have been better. What I disagree with, however, is that in the Western view — and certainly in Canada’s — human rights are universal; any compromise on their validity would only invite further erosion of the principle and allow Beijing to get away with murder. Furthermore, as I’ve argued before, a soft, compromising approach to human rights in China ultimately ends up transforming us: We saw this during the Olympic Games in Beijing, with various intelligence agencies sharing intelligence with the Beijing security apparatus; at various venues during the Olympic torch journey, which resulted in massive police deployments in otherwise liberal cities around the world; and in Taiwan during the visit in November of ARATS Chairman Chen Yunlin (陳雲林), Taipei’s refusal to allow the Dalai Lama to visit, and, more recently, in its silence prior to the execution of suspected spy Wo Weihan (伍維漢) and during the security clampdown in Xinjiang.

All of these — and especially Taipei’s silence — were meant as compromises. What did this result in? The victims of Chinese repression only felt more abandoned than ever. I don’t often agree with Harper, but when, speaking at the APEC summit in 2007, he said that he would not sell out human rights to the “almighty dollar” in his relations with Beijing, he was right. This is not to say that a hard line on China’s human rights record would fare any better in securing the release of imprisoned individuals like Mr. Celil, but at least we wouldn’t be selling our souls in the process.

Ultimately, Celil is still in jail because Canadian diplomats had no stick with which to bring Beijing into line, while Canada craved the carrot that China wiggled at Ottawa’s nose.

Compromising on human rights is a slippery slope. One that door is opened, Beijing is sure to stick its foot at the bottom and widen the wedge. Leave it open long enough, and we might fall into the other room. If, as is often the case, “pragmatism” in one’s relations with China means exposing oneself to some sort of venereal disease of the soul, then I’d rather protect myself with the prophylactic of unwavering principles.

Sunday, August 23, 2009

UN sends team to [Taiwan]

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs said today that the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) would be sending a team within a week to help with reconstruction in the wake of Typhoon Morakot. Great! Finally, the UN admits to the existence of Taiwan and will even be sending experts, albeit belatedly, to help Taiwanese in the south. This, we are told, will be the first time the UN sends a humanitarian delegation (of three) to Taiwan since the 921 Earthquake.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs said today that the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) would be sending a team within a week to help with reconstruction in the wake of Typhoon Morakot. Great! Finally, the UN admits to the existence of Taiwan and will even be sending experts, albeit belatedly, to help Taiwanese in the south. This, we are told, will be the first time the UN sends a humanitarian delegation (of three) to Taiwan since the 921 Earthquake.But wait, keep that outburst of optimism under your hat for a minute. Here’s why: On Aug. 12, the UN News Center filed the following story about Typhoon Morakot:

Senior UN official calls for urgent measures to mitigate impact of landslides

Action must be taken to mitigate the impact of landslides such as those triggered recently in parts of East Asia by Typhoon Morakot, which has reportedly buried entire villages and killed scores of people, a senior United Nations official working on disaster risk reduction stressed today.

“As this week’s tragic events in East Asia show once again, people living on unstable slopes and steep terrains are particularly at risk from landslides in the wake of torrential rain and flooding,” said Margareta Wahlström, who heads the UN International Strategy for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR).

“While landslides are hard to predict, people living in landslide-prone areas can be alerted in advance if there are monitoring and warning systems in place to measure rainfalls and soil conditions,” she added.

Ms. Wahlström underlined the urgency of these measures by pointing to population growth and the urbanization of steep hillsides, along with the predictions by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) of more intense rainfalls in the future, leading to increased instability of slopes and making more people vulnerable to landslides.

She also highlighted the case of Hong Kong, where a ‘Slope Safety System’ introduced in the mid-1970s has resulted in a 50 per cent fall in casualty rates from landslides since 1977, and is targeting a further reduction — to 75 per cent — by 2010.

In addition, an early warning system implemented in Costa Rica, which trained some 200 people in disaster preparedness and 30 people as radio operators, saw a dramatic improvement in the response to a second landslide in nine months, saving hundreds of lives.

“Landslides are a growing problem in many countries, but, as these examples show, people living in landslide-prone areas can be better protected,” said Ms. Wahlström, who is also Assistant-Secretary-General for Disaster Risk Reduction.

OK. There you have it. All 297 words about Morakot. Not a single mention of Taiwan. Instead, what we have are “tragic events in East Asia.” About 500 people died in Taiwan, and yet in its call for action, the UN writes instead about Hong Kong — and Costa Rica, for crying out loud! OCHA’s Situation Report #1 on Typhoon Morakot, dated Aug. 19, meanwhile, opens with the sentence “On 7 August 2009, landfall resulting from Typhoon Morakot hit the south-east coast of mainland China and the island of Taiwan,” before embarking on a long description of the damage in China. Throughout the report, the UN refers to “the battered island of Taiwan” and relies extensively on Xinhua news agency, a Chinese state-sponsored and controlled organ, for its information (no agency or news outlet in Taiwan is mentioned). The “Funding” section of the report briefly mentions that 59 countries have offered assistance and that Japan has pledged US$1 million. But the section mainly consists of a detailed description of financial help from China, which actually reads as if it had been drafted by a seasoned propagandist in Beijing:

On 19 August, Xinhua news agency reported that organizations and individuals in the mainland have donated about CNY 176 million (USD 26 million) to the typhoon battered island for disaster relief. The mainland had also donated CNY 25 million (USD 3.6 million) worth of relief materials to the island, including prefabricated houses, sleeping bags, blankets and sterilizers … On 18 August, the Hong Kong Special Administration Region (SAR) government and Macao SAR government have also sent TWD 210 million (USD 6.3 million) and TWD 40 million (USD 1.2 million) respectively … Donations are also being channeled through the TRCO. The Red Cross Society of China (RCSC) headquarters issued CNY 15 million (US$ 2.1 million) to support the TRCO in providing relief assistance to communities. Guangdong, Shanghai and Fujian branches of the RCSC further supplemented their headquarters’ support with CNY 1 million (US$ 146,150) each to TRCO for relief efforts. IFRC in New York has channeled private donations worth US$ 500,000 to the TRCO as well.

All of which overemphasizes the role China is playing in reconstruction while giving the impression that Taiwan is part of China. Why the focus on the type of aid provided by China? Why not a similarly detailed account of US assistance?

Given China’s weight at the UN, added to the world body’s spinelessness, it’ll be interesting to see how the UN team’s visit will be characterized (quite expectedly as UN assistance to China). We can also expect that the officials will have to stop in China first before crossing the strait to Taiwan. Now, in light of the UN’s long snub of Taiwanese identity, what welcome should be reserved those “experts” when they arrive in Taiwan — unbridled gratitude, or eggs?

In all fairness to MOFA (and the UN), a well-placed source informs me that the visit by UN experts is actually a sign that the ministry is making inroads at the UN, and that the world body’s omission of the name Taiwan is the result of the balancing act it must do to secure its interests and those of Taiwan. According to the source, many prestigious health professionals organizations rallied in Taiwan’s favor during the WHO campaign (in which our scapegoat, Andrew Hsia, allegedly played a key role), which effectively forced Beijing’s hand. The UN group, which will be in Taiwan to assess what needs to be done for reconstruction and to prevent future catastrophes like this from recurring, could “kick the ass” of legislators who had blocked a Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)-initiated bill that was addressing the issue of mismanagement of mountainous areas and the environment in general, the source said. The prestige conferred by their role in OCHA could very well compel the central government, whose image has suffered tremendously as a result of its poor handling of Morakot, to revisit the recommendations made by the DPP and act accordingly. Let’s see how this plays out, and if the recommendations made by the UN trio are adopted by the central government. It would be no small irony if the UN recommendations turned out to be similar to those made by the DPP...

Saturday, August 22, 2009

Kuo Kuan-ying shares his thoughts

Remember Kuo Kuan-ying (郭冠英), the official at Taiwan’s representative office in Toronto who was recalled and fired after it was found that he had penned a series of articles basically denying the right of Taiwanese to exist as a people? Well, he’s back in the media — and he hasn’t changed his tune. Attending a New Party event, Kuo was approached by the media to share his thoughts about CNN’s coverage of the Taiwanese government’s handling of Typhoon Morakot. CNN, the still facial-tick-prone Kuo said, is “a tool of imperialists from beginning to end.” It gets better: “CNN has always stood with the imperialists. It did so during the uprising in our country’s [sic] Tibet and now it’s like that again in the Province of Taiwan [sic]. It’s malicious.” That the New Party would still count such people in its midst speaks volumes.

Remember Kuo Kuan-ying (郭冠英), the official at Taiwan’s representative office in Toronto who was recalled and fired after it was found that he had penned a series of articles basically denying the right of Taiwanese to exist as a people? Well, he’s back in the media — and he hasn’t changed his tune. Attending a New Party event, Kuo was approached by the media to share his thoughts about CNN’s coverage of the Taiwanese government’s handling of Typhoon Morakot. CNN, the still facial-tick-prone Kuo said, is “a tool of imperialists from beginning to end.” It gets better: “CNN has always stood with the imperialists. It did so during the uprising in our country’s [sic] Tibet and now it’s like that again in the Province of Taiwan [sic]. It’s malicious.” That the New Party would still count such people in its midst speaks volumes.Kuo’s interview can be accessed on YouTube.

Morakot two weeks on: ugliness and beauty

Typhoon Morakot revealed to the world that the central government in Taiwan was unprepared, disorganized and, on occasion, aloof, while demonstrating the unenviable political position in which Taiwan finds itself as a result of China’s territorial claim. Heads in the administration of President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) have rolled, though it is evident that the individuals who “offered” to resign (e.g., Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrew Hsia [夏立言] and Minister of National Defense Chen Chao-min [陳肇敏]) ultimately should not bear responsibility for the government’s failure to react in time, as the decisions that were not made — or that were made, but belatedly — rested with their superiors in the executive.

Typhoon Morakot revealed to the world that the central government in Taiwan was unprepared, disorganized and, on occasion, aloof, while demonstrating the unenviable political position in which Taiwan finds itself as a result of China’s territorial claim. Heads in the administration of President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) have rolled, though it is evident that the individuals who “offered” to resign (e.g., Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrew Hsia [夏立言] and Minister of National Defense Chen Chao-min [陳肇敏]) ultimately should not bear responsibility for the government’s failure to react in time, as the decisions that were not made — or that were made, but belatedly — rested with their superiors in the executive.This buck-passing, used to shield the individuals at the very top, does not appear to have succeeded in deceiving the electorate and the media, however, as both continue to target Ma and his immediate aides for their criticism. In fact, even people who, under normal circumstances, are pan-blue supporters are crying foul over the government’s unwillingness to own up to its mistakes. A senior official at a well-established foreign academic institution in Taipei with strong connections to the Taiwanese government earlier this week commented on the Hsia case, basically saying that he’d known Hsia for 25 years, that he’s “a good guy,” competent, and would never have done the things he is now allegedly stepping down for. I have heard similar comments about Hsia by other people, including some who worked in the same agency. The ramifications this will have on continued support for the pan-blue camp — at least in its current iteration under the Ma leadership — remain to be seen; but one thing is sure: its image has suffered permanent damage, and there is no knowing if, at some point, some of the officials who have been unjustly forced to take the blame for the executive’s failings will not blow the whistle.

Still, it’s not all bad. While the government dithered and played politics, society hit the ground running and mobilized in commendable fashion, launching rescue efforts, raising funds and providing various kinds of support. Without proper oversight, this spontaneous outburst of generosity created overlap and may at times have been chaotic, if not wasteful, but there is no doubt that Taiwanese of all stripes cast aside politics, “ethnic” differences and the great north-south divide in this hour of need. In fact, compounded by government inefficiency, the argument could be made that Morakot rallied Taiwanese around the flag and brought people together far more effectively than any political rally by the pan-green camp could have hoped to achieve. A positive offshoot of this disaster, then, could be that the relative ease with which the Ma administration has passed agreement after agreement tying Taiwan’s economic survival to China — in effect turning economic integration into political integration — may no longer exist, and that opposition to his pro-China policies will henceforth be fiercer. The criticism of Ma that has suddenly materialized in foreign media, meanwhile, could also elevate the barriers he faces in his misguided quest for “peace” with Beijing. Though necessary when dealing with a regime such as that in Beijing, those hurdles had for the most part been absent. Hopefully, this will no longer be the case.

Also moving has been the foreign expression of solidarity, with numerous countries offering humanitarian assistance and individuals seeking to do their part. Just today, a number of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies — many of which are quite poor — organized a fundraising event in Taipei to help out. Many individuals, meanwhile, have sought to do something to help; groups of expatriates went south to participate in cleanup efforts, while others took photos, shot videos or reported on what was going on, helping to tell the story to the world. People abroad have approached the media and bloggers asking about which agency they should donate to. A friend of mine who works at the Liberty Times (my employer’s sister newspaper) was contacted by a Dutch friend who works in Hong Kong if a relief agency in Taiwan would be willing to help him out, as he was offering to fly over to Taiwan and volunteer for a week. In another instance, someone at my newspaper organized to have grapes cultivated by an Aboriginal community shipped to Taipei; no middle man: all the money will go back to that community to help with reconstruction. Many boxes were sold.

Amid the ugly politics that have characterized the past two weeks, many green shoots of love and altruism were seen, and we must cherish those. I’ve often heard people say that for some inexplicable reason, there’s a love story between individuals and Taiwan. Not only is it a sentiment that I share, but it has been in fully display over the past 14 days.

Thursday, August 20, 2009

Beijing’s stinking hypocrisy

“The difficulties Taiwan compatriots are facing [in the wake of Typhoon Morakot] mean the same to us,” Chinese President and Chairman of the Central Military Commission Hu Jintao (胡錦濤) told a delegation of ethnic minorities from Taiwan led by Non-Partisan Solidarity Union Legislator May Chin (高金素梅) yesterday. “We will continue helping them in rescue and relief as well as support them in rehabilitation.”

“The difficulties Taiwan compatriots are facing [in the wake of Typhoon Morakot] mean the same to us,” Chinese President and Chairman of the Central Military Commission Hu Jintao (胡錦濤) told a delegation of ethnic minorities from Taiwan led by Non-Partisan Solidarity Union Legislator May Chin (高金素梅) yesterday. “We will continue helping them in rescue and relief as well as support them in rehabilitation.”“We share the same feeling with Taiwan compatriots, especially the ethnic minorities, who suffered serious life and property loss in the recent disaster. We are very much concerned” (胡锦涛说,不久前,台湾遭受了历史罕见的台风灾害,台湾同胞的生命财产蒙受了重大损失,特别是一些台湾少数民族同胞受灾严重。我们对此感同身受,十分关切,十分牵挂。在这里,我谨代表大陆同胞,向遭受台风袭击的台湾父老乡亲致以深切慰问,对不幸遇难的台湾同胞深表哀悼。) the state-controlled People’s Daily newspaper quoted the leader as saying.

According to the paper, China has donated about 176 million yuan (US$26 million) and 25 million yuan in disaster relief material to Taiwan, including 10,000 sleeping bags, 10,000 blankets and 1,000 sterilization appliances.

All of this would be heartwarming were it not for the fact that Beijing is exploiting a natural catastrophe for propagandistic purposes (and so is Taiwan’s representative office in Denmark, which issued a press release celebrating China’s humanitarian assistance without making a single mention of any of the other donors, including the US).

The hypocrisy, of course, lies in the fact that the same Chinese leadership that “share[s] the same feeling with Taiwan compatriots” has for years threatened to attack Taiwan should the latter move toward formal independence — or even drag unification talks for too long. It is the same leadership that passed the “Anti-Secession” law making it “legal” to use force in such an eventuality. It is the same leadership that, back in 2003, prevented the WHO from immediately sending health experts to Taiwan during the SARS crisis. It is also the same leadership that 10 years ago after the catastrophic 921 Earthquake in central Taiwan, was forcing international emergency teams to pass through China first before going to Taiwan, thus causing unnecessary — and costly — delays. It is the same leadership that has long prevented Taiwan from joining multilateral bodies, which has ostracized Taiwan and mitigated its efforts to contribute to, and learn from, shared global expertise on a number of issues (surely, if Taiwan were allowed by Beijing to exist as a normal country, its Red Cross would be part of the International Committee of the Red Cross rather than an independent entity).

The human cost of Morakot, though severe, pales in comparison to what would happen if China launched an invasion, or even just a missile attack, against Taiwan. Even as preparations were being made last year to launch a new round of meetings between the Straits Exchange Foundation and the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Strait, the latter entity’s chairman, Zhang Mingqing (張銘清), was saying that there would be no war in the Taiwan Strait as long as Taiwanese gave up their aspirations for independence, a veiled threat if ever there was one.

(China’s Taiwan Affairs Office Minister Wang Yi (王毅) reportedly gave Chin a 20 million yuan (US$2.9 million) check for “relief aid,” which has drawn accusations from both main political parties in Taiwan, as well as Aborigines, because foreign aid is by law supposed to be channeled through the Ministry of the Interior, the Straits Exchange Foundation or the Red Cross. While there is no law that forbids individuals from receiving donations, it will be impossible to make sure that the money is properly used. Chin has also come under fire for apparently playing into Beijing’s propaganda game. Note, too, that this is the same Chin who left for Japan in the midst of Typhoon Morakot to lead a protest at Yasukuni shrine. Within one week, she’s managed both to portray Japan as the “enemy” and China as a “friend”... and got paid for it.)

We should not politicize humanitarian help, and all of it is technically welcome. But when a state threatening military aggression uses this for a propaganda campaign, and when its leader — and head of the CMC, China’s top military decision-making body — makes a mockery of human compassion by claiming to “share” the pain of Taiwanese in this hour of need, we cannot help but smell politics. And it stinks.

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

Nature is Taiwan’s No. 1 enemy, defense minister offers to resign, quid pro quos?

During his press conference with international media on Tuesday, President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) surprised many when he said that “Now our enemy is not necessarily the people across the Taiwan Strait, but nature,” adding: “In the future, the armed forces of this country will have disaster prevention and rescue as their main job. So, they have to change their strategy, tactics, their personnel arrangements, their budget and equipment.”

During his press conference with international media on Tuesday, President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) surprised many when he said that “Now our enemy is not necessarily the people across the Taiwan Strait, but nature,” adding: “In the future, the armed forces of this country will have disaster prevention and rescue as their main job. So, they have to change their strategy, tactics, their personnel arrangements, their budget and equipment.”To this end, Ma said, Taipei, would reduce the number of UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters it intends to buy from Washington from 60 to 45, which would free approximately US$300 million to acquire helicopters and other equipment designed to deal with disaster relief.

At the same press conference, however, Minister of National Defense Chen Chao-min (陳肇敏) said “Disaster and rescue relief [are] one of the primary missions of the military” rather than the main one, which appears to contradict Ma’s comments.

Resignation

Less than a day later, news broke that Chen had offered to resign over the government’s slow response to the Typhoon Morakot emergency. This, of course, will raise speculation as to whether Chen was forced to step down so that he, like Andrew Hsia (夏立言) the day before, could be a fall guy for the Ma administration, or perhaps that it was related to disagreement over what the Ministry of National Defense’s main priority should be — the threat of a Chinese invasion, or the forces of nature. Based on the discrepancies in Ma and Chen’s comments at the press conference, we can assume that the two men do not see eye-to-eye on what ought to be the military’s priority. Ma’s apparent shift, added to the removal of 15 Black Hawk helicopters from the shopping list, other cuts in the military and the watering down of military exercises such as the annual Han Kuang, all point to his assessment that China no longer represents a fundamental threat to national security. This, of course, despite Beijing’s refusal to remove the 1,500 short-range missiles it targets at Taiwan and its continued modernization of the People’s Liberation Army with unrelenting focus on a Taiwan contingency.

What should be immediately clear from Ma’s announcement is that the focus on nature as Taiwan’s No. 1 enemy is a tactical reaction to mounting criticism rather than a paradigm shift in national defense posture reached within the national security apparatus after a careful risk and threat assessment. Secondly, as any military decision is contingent on approval from the commander in chief — that is, the president — it was not Chen’s prerogative to decide when rescue operations should be launched. As such, Chen’s superiors, not him, should be shouldering the blame on this.

It is not impossible, therefore, that Chen’s “offer” to resign is in fact the result of the Ma Cabinet using the pretext of Morakot to rid itself of yet another military official who continues to see China as the principal threat, which dovetails with purges, under the guise of corruption probes, that appear to have overwhelmingly focused on military officials promoted during the Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) administration (this is not to say that Chen Chao-min was on good terms with Chen Shui-bian, given the slander case that the latter filed against him regarding comments he made about the 319 shooting incident).

It is not impossible, either, that cuts in military acquisitions could be a quid pro quo for Beijing’s acquiescence in the deployment of US military aircraft and personnel in Taiwan.

Three Noes

Finally, Ma also announced that the national Double Ten (Oct. 10) celebrations, as well as a planned trip to diplomatic allies in the South Pacific, would be canceled because of the disaster. While a celebratory mood would indeed be improper so soon after the disaster, there nevertheless remains a need for the nation to rally around the flag and celebrate, if perhaps in more sober fashion, what it means to be Taiwanese. But no. Celebrations will be canceled, diplomacy will be frozen, and for the first time in years Taiwan will not bid for membership at the UN.

Oddly enough, all three developments will be most welcome in Beijing, as they all incorporate elements of Taiwan’s sovereignty. Quid pro quo, again?

The Chinese elite fails at democracy, does not get Taiwan

Jian Junbo’s article “Taiwan’s ‘opportunist’ president alters tack,” published in Asia Times Online on Aug. 11, unwittingly provides a solid argument against the unification of Taiwan and China, as it clearly demonstrates how the otherwise educated Chinese elite like Mr. Jian, an assistant professor at the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University in Shanghai, completely fails to understand what Taiwanese think and what democracy is all about. In that respect, this is a useful article, in terms of serving as an eye-opener for those in Taiwan who support unification or believe that the younger of generation of Chinese, which has seen more of the world, is becoming more democratic.

Jian Junbo’s article “Taiwan’s ‘opportunist’ president alters tack,” published in Asia Times Online on Aug. 11, unwittingly provides a solid argument against the unification of Taiwan and China, as it clearly demonstrates how the otherwise educated Chinese elite like Mr. Jian, an assistant professor at the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University in Shanghai, completely fails to understand what Taiwanese think and what democracy is all about. In that respect, this is a useful article, in terms of serving as an eye-opener for those in Taiwan who support unification or believe that the younger of generation of Chinese, which has seen more of the world, is becoming more democratic.Ironically, many Taiwanese would agree with Mr. Jian’s opening statement, that President Ma Ying-jeou is an “opportunist” who “appears to lack foresight and strategy, with hesitation and self-contradiction manifest in his mainland policy.” They would do so, however, for altogether divergent reasons, as we shall see later.

For now, let us take a close look at the pledge Ma is alleged to have made and the reasons why, from Mr. Jian’s perspective, Ma is contradicting himself. Jian argues that “fresh in the people’s minds” — this would be in November last year — Ma made a “solemn pledge” to “uphold the ‘one China’ principle stipulated in the [Republic of China] constitution.” What Ma actually “pledged” was to abide by the constitution — which was amended in 1991 and reads that cross-strait relations are a “state-to-state” or “special state-to-state” relationship — and the so-called “1992 consensus” for the SEF-ARATS talks, which refers to “one China, separate interpretations” or alternatively “one China, respective interpretations.”

We should remember that the “1992 consensus” was crafted (be a small group of individuals rather than through a democratic process) so that the Taiwanese leadership would have room to maneuver, and provided the very flexibility that Mr. Jian now perceives as “opportunism” and contradictory. It also implies recognition, on Taiwan’s side, that China will not sit down for talks unless Taipei refers to “one China.” In other words, the term is being forced on Taipei as a precondition for talks. What it does not mean, however, is that Taiwanese accept that there is only one China and that Taiwan is part of China (a tiny minority does). This is an important distinction that Mr. Jian fails to make.

Mr. Jian then accuses Ma of saying that Beijing should recognize the realities across the Taiwan Strait, that there is the ROC and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), or “two Chinas.” What gall, on Ma’s part, to state what is, indeed, a reality! (To get even closer to reality, we’d have to say that there is, indeed, only one China, and that is the PRC, while that concept called the ROC is in fact Taiwan, a sovereign country across the Taiwan Strait.)

All this, added to Jian’s allegation that Ma told visiting Dutch parliamentarians on Aug. 2 that he doesn’t intend to hold any political talks with Beijing, is evidence, in the author’s mind, that Ma “is a person who cannot adhere to one principle from beginning to end. Based on a number of speeches and interviews Ma has given, there is no indication that Ma does not intend, at some point, to discuss political issues with Beijing. As has already been clearly explained by his administration, however, and as has been the case since the secret cross-strait talks and SEF-ARATS meetings began in the early 1990s, Taipei prefers to negotiate on less contentious issues first and to keep difficult political matters for last. But Jian has no time for this. Ma is an “opportunist” who is “dizzy” with his cross-strait successes, which are making him speak “thoughtlessly” (meaning “irrationally,” the same kind of accusations that have so often been leveled at supporters of Taiwanese independence, as opposed to the “rationalism” of those who support unification).

Ma’s wavering and failure to adhere to his “pledge,” in Jian’s view, indicates that he does not support “one China,” which in Beijing’s paranoid view is tantamount to supporting independence. The author also sees evidence of a Ma volte-face in his request that Beijing remove the 1,500 short-range missiles it aims at Taiwan before any talks on a peace accord can be held. Jian writes that Beijing has “no problem in practice with removing those missiles … as long as Taipei formally agrees to stop and even fight any form of support for Taiwan’s independence.”

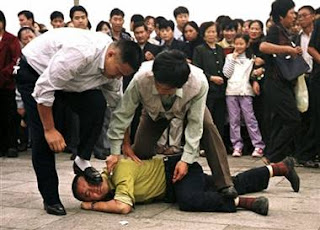

Jian conveniently forgets that Ma has also pledged not to declare or support independence for Taiwan. Anyone who has even but a superficial understanding of the Ma administration would know that there is no chance that it will support, let alone assist, the Taiwanese independence movement. However, as it is an elected government in a democracy, it simply cannot engage in the “stopping” and “fighting” of TI supporters Jian would ostensibly see as evidence of Ma’s commitment to “one China.” Taiwan isn’t China, where brute force and police-state measures are used to fight, stop and silence dissidents.

What this ultimately means for Ma’s “pledge” to abide by the “one China” principle while not supporting independence is that as president in a democracy, he must perform a balancing act. Whether Jian likes it or not, Ma cannot simply ignore legislative and presidential elections and forge ahead with his cross-strait policies. Doing so would be political suicide. In fact, it would risk undermining the very political end Mr. Jian so obviously desires. As such, Ma is forced to cater to various sociopolitical factions — including factions within his own party, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). As happens in any democracy, this requirement to cater to, or at minimum appease, factions (political, social, economic, external) with different objectives forces leaders to adopt a more centrist position, which in Taiwan’s case means the “status quo.” It also means saying things that may sound contradictory, or adopting policies that, prima facie, may appear unwise, as was the intensification of cross strait economic exchanges at a time when China was strengthening its military posture, which occurred while the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) under president Chen Shui-bian was in power.

Jian continues by writing that “What ‘One China’ means in Beijing’s view is not the PRC, nor of course the ROC, but a nation with independent sovereignty covering both the mainland and Taiwan and a history of 5,000 years. It is based on such a vague definition of ‘one China’ that detente on the strait in the past year has become possible.”

What he omits, however, is that this “one China” would comprise unequal partners, in which the PRC is the predominant force and the ROC a mere subject, which has implications for the desire of Taiwanese to unify with China (not to mention the authoritarian nature of the PRC leadership, or the fact that Taiwan has been ruled separately for at least 114 years).

“As a graduate of Harvard University’s Faculty of Law,” Jian writes, “Ma Ying-jeou must understand clearly that world leaders should not easily be swung by public opinions in society if he is really interested in their best interests. The fact that some Taiwanese are advocating for the island’s independence cannot be a legitimate excuse for Ma Ying-jeou to refuse political dialogue with Beijing or deny ‘one China.’”

In this passage we find Jian unashamedly exposing his total lack of understanding of democracy. In democratic systems, leaders are inevitably swayed by public opinion, and those who refuse to do so are swiftly phased out through electoral retribution. The claim that strong leaders know what is in people’s “best interests,” meanwhile, not only is undemocratic, but derives from a sympathetic view of authoritarianism, which Taiwan thankfully managed to rid itself of after 40 years under such rule. Observations such as “When given the opportunity, [Ma] should use his authority and power to push for cross-strait political mutual trust. Now, since he will soon take the chairmanship of … KMT, he should think less of his own re-election in 2012 and launch a historic meeting with Chinese leader Hu Jintao” also demonstrate Jian’s disregard for democracy.

His comment, meanwhile, that “some Taiwanese are advocating for the island’s independence” is misleading. “Some” gives the impression that there are only a handful, while masking the fact that close to 90 percent of people in Taiwan support neither independence nor unification — in other words, they want the “status quo” to continue.

Facing this, as well as mounting criticism that Ma is going too fast in his cross-strait policies, or that he is making Taiwan dangerously dependent economically on China, Ma is compelled to adopt a more centrist political stance and to proceed more slowly. Furthermore, there are signs that the Ma administration has been less than transparent, and sometimes altogether undemocratic, in its dealings with China, which if proven will further add to domestic pressure. What from across the strait is seen as a slow, wavering and “opportunist” Ma is, on the other side, seen as “selling out” to China and endangering the sovereignty of Taiwan by proceeding too fast and giving too much.

And yet, Jian warns that Ma should focus less on his reelection bid in 2012 (or that of his officials, who are entirely effaced though Jian’s focus on strong authoritarian leadership) and accelerate the pace of negotiations, showcasing the same impatience displayed by Jiang Zemin in the 1990s, who said that talks on unification could not go on indefinitely.

Jian concludes by writing that “If Ma thinks the future of Taiwan should be decided by Taipei and the country’s 23 million Taiwanese, then he must also realize that cross-strait relations are also partly decided by Beijing and China’s 1.3 billion Chinese, not just by Taiwan.”

This is just the kind of friendly reassurances Taiwanese need from their Chinese “compatriots” — if you decide your own future democratically, we’ll use the crushing weight of 1.3 billion Chinese (and its military, we can assume) to bring you back in line, to force you to love us.

Let us hope that Mr. Jian, who is now a visiting scholar in Denmark, learns a thing or two about democracy before he pens his next article pretending to know what’s best for Taiwanese and their leaders.

This response was published in Asia Times Online on Aug. 21.

Tuesday, August 18, 2009

Morakot claims its first political victim

During separate press conferences with local and foreign media today, President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) announced that Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrew Hsia (夏立言) — who came under fire over a leaked memo by the ministry ordering offices abroad to refuse aid in the wake of Typhoon Morakot — had tendered his resignation. That Ma would make this information public implies that Hsia’s resignation has, for all intents and purposes, been accepted.

During separate press conferences with local and foreign media today, President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) announced that Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrew Hsia (夏立言) — who came under fire over a leaked memo by the ministry ordering offices abroad to refuse aid in the wake of Typhoon Morakot — had tendered his resignation. That Ma would make this information public implies that Hsia’s resignation has, for all intents and purposes, been accepted.While the fact that heads are starting to roll following the central government’s amateurish handling of the emergency is a welcome development, it is also evident that Hsia is being made a scapegoat. Admittedly, Minister of Foreign Affairs Francisco Ou (歐鴻鍊) was not in the country when the decision to refuse aid was made, but it is hard to believe that he would not have been contacted, or that he did not provide guidance on the matter. Furthermore, Ou was not on leave, but on a diplomatic mission that sources claim included Jordan and the Czech Republic. In other words, Ou was still active and should have been kept in the decision-making chain. As such, Ou should also be reprimanded for his ministry’s misguided — and likely deadly — policy.

A well-placed source, however, informed me that the memo dictating the refusal of aid came from above Hsia (who probably did not have the authority to make such a decision), and probably even higher than Ou, which means that it was either the National Security Council or the Executive Yuan. Why they would have ordered this remains a mystery and points to the external political considerations I discussed in previous articles.

The senior public officials who are behind this decision, therefore, are likely to remain unaccountable, while Hsia, who either was in over his head or was ordered around, is being served as a sacrificial lamb to an angered Taiwanese public. Whether this first political victim will be sufficient to appease Taiwanese remains to be seen.

Another possible reason for the decision to delay the approval of foreign aid, as a source indicates, is that the top leadership did not know what kind of material assistance was required and therefore did not want countries to start sending planeloads of unnecessary material. What allegedly followed was an internal screw-up and departure from the internal chain of approval for the memo, which may have bypassed both a section director-general for review of the draft, and Hsia altogether. If this is true, then Hsia is being forced to resign for something he did not do.

Regarding the possibility of external political reasons as to why the top leadership (EY, NSC, Premier, etc) would have instructed MOFA to inform its missions abroad to say no to offers of assistance, I do not think that Beijing would have ordered Taipei to reject foreign aid, and this is something I have been arguing since the beginning. After all, Beijing does not stand to gain anything by Ma facing criticism or his administration being undermined by the situation. In fact, what China needs is a strong, popular Ma who can forge ahead with his cross-strait policies and thereby bring Taiwan closer to unification.

What remains possible, however, is that on the Taiwan side, policy-makers decided to wait for a green light from Beijing for fear of “angering” it by opening its doors to foreign aid, especially from the US and Japan. In other words, misperceptions by Taipei of the importance Beijing paid to the symbolism of foreign assistance in Taiwan, rather than Chinese interference in the process, could help explain the decision at the top to delay aid approval and instruct MOFA to adopt that policy.

Hsia is the first fall guy, over a development that in the end was far less consequential than the more pressing question of why it took so long for the military to deploy in the south to launch rescue operations. Ma can claim all he wants that heavy rain over three days prevented the deployment of helicopters, but the fact remains that rain or no rain, there should have been boots on the ground—and there weren’t. Whose head will roll for that one?

Generous, eh?

Despite the seriousness of the disaster in southern Taiwan following the passage of Typhoon Morakot on Aug. 8, comparisons with the Sichuan Earthquake of May 12, 2008, should be made with the greatest of caution, as the magnitude of the catastrophes differ substantially. This notwithstanding, the damage in Taiwan is not inconsiderable, and help is needed.

Despite the seriousness of the disaster in southern Taiwan following the passage of Typhoon Morakot on Aug. 8, comparisons with the Sichuan Earthquake of May 12, 2008, should be made with the greatest of caution, as the magnitude of the catastrophes differ substantially. This notwithstanding, the damage in Taiwan is not inconsiderable, and help is needed.I was therefore overjoyed to learn on Monday that the Canadian government, which until then had been conspicuously silent on Morakot, had finally announced it would be donating to the Taiwan Red Cross Society — that is, until I found out how much it was contributing: a measly C$50,000 (US$45,000), with about C$2,200 more from locally engaged staff and officials at the Canadian Trade Office and 200,000 water-purification tablets. This from a G8 country with a GDP of US$1.07 trillion in 2008.

Contrast this with the C$60 million that Canadians donated to China after Sichuan, of which half came from private donations and the other half from the Canadian government (it also donated C$11.6 million to Myanmar after Cyclone Nargis). Again, there is no debating that the Sichuan Earthquake was far more damaging and deadly than Typhoon Morakot, but the difference is nevertheless striking, especially so when one considers the amount of money Beijing spends on its military annually, the size of its economy and its tremendous foreign reserves. Yes, people in Sichuan are extremely poor, but this is mostly the result of inequitable wealth distribution, which doesn’t apply to Myanmar.

Democratic Taiwan, which threatens no one and which has a respectable history of helping other countries in time of need, receives peanuts from Canada, an important trading partner, source of tourism and home to many Taiwanese. Authoritarian China, which locks up dissidents, threatens neighbors, undermines civil securities in resource-rich countries and kills Tibetans and Uighurs by the hundreds, receives aid by the millions. Go figure.

As a Canadian who has made his home in Taiwan and has been given so much by the beautiful Taiwanese people, I feel ashamed of my government’s less than generous aid to Taiwan in its hour of need.

Monday, August 17, 2009

Blunders, buck-passing and a web of lies

First it was a “typographical error” in the missive transmitted to Taiwanese representative offices abroad, which conveyed the instruction that all offices were to turn down offers of foreign assistance in the wake of Typhoon Morakot. That “error,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) officials later claimed, mislead officials into thinking that the refusal of aid was permanent, rather than “temporary.” While a well-placed source affirms that the decision came from someone above Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrew Hsia (夏立言), who was acting in the absence of Foreign Minister Francisco Ou (歐鴻鍊), the rationale for that decision, or what would make a “temporary” ban any better, has yet to be communicated publicly.

First it was a “typographical error” in the missive transmitted to Taiwanese representative offices abroad, which conveyed the instruction that all offices were to turn down offers of foreign assistance in the wake of Typhoon Morakot. That “error,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) officials later claimed, mislead officials into thinking that the refusal of aid was permanent, rather than “temporary.” While a well-placed source affirms that the decision came from someone above Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrew Hsia (夏立言), who was acting in the absence of Foreign Minister Francisco Ou (歐鴻鍊), the rationale for that decision, or what would make a “temporary” ban any better, has yet to be communicated publicly.Then it was President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) saying that he’d never meant to criticize victims of the disaster for not evacuating affected areas quickly enough.

As if the above were not clear enough signs of a bungled reaction to the disaster, the Presidential Office, the Ministry of the Interior, the Ministry of National Defense, MOFA, the fire department, local governments and the premier have all engaged in buck-passing (usually top-down), giving the impression that nobody’s in charge. Compounding that perception was a press conference on Sunday, where the Central Emergency Operation Center commander, Mao Chih-kuo (毛治國), was unable to provide answers to questions by foreign reporters on such matters as the body count in Xiaolin Village or the type of assistance expected from the US and Japan.

The last straw (or is it?)

Then on Monday, the Government Information Office sent a message to the Taiwan Foreign Correspondents’ Club (TFCC) with the instruction that all foreign correspondents who had signed up for a press conference by Ma with international media scheduled for Tuesday should provide their questions beforehand. Fearing that complying with this directive would undermine the credibility of foreign reporters as well as their ability to do their job and speak truth to power, the TFCC replied with a statement in which it made clear its unwillingness to comply. Soon afterwards, the GIO responded by saying that it had been “misunderstood” and that the directive was not mandatory.

Are we now to believe that the GIO, whose main purpose is to communicate information, is unable to make itself understood? More likely, the GIO meant what the directive said, tested the water, and when it saw trouble brewing on the horizon, it retracted it, relying on the by-now exhausted “we were misunderstood” excuse of the Ma administration.

Either no one’s in control, or officials are being caught in their own web of lies. Either way, it makes the administration look staggeringly incompetent.

Sunday, August 16, 2009

Sunday notes on Morakot emergency

There is a very moving passage in Chen Guidi and Wu Chuntao’s book Will the Boat Sink the Water: The Life of China’s Peasants, in which elderly peasants who, after months of seeking justice in their village, decide to go to the township and county level to beg officials to intervene, only to be turned down. At one point, in a blatant reversal of cultural ethics, the elderly are described as kneeling in front of young government officials, who remain standing and ignore their pleas. Little did I know that a few days after reading this passage, Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) would practically behave like those young, callous officials after Taiwanese asked for help amid the devastation brought by Typhoon Morakot. In scene after scene, Ma has looked annoyed, impatient, and would often hide behind a wall of security officials as Taiwanese sought to approach him. On some occasions, elderly Taiwanese fell on their knees, and Ma remained standing, displaying a level of cultural insensitivity that will not be forgotten anytime soon. In that regard, Ma’s wife, first lady Chow Mei-ching (周美青), has fared much better, going down on her knees to bring comfort to grieving individuals and seeming far more at ease among ordinary people than her husband has.

There is a very moving passage in Chen Guidi and Wu Chuntao’s book Will the Boat Sink the Water: The Life of China’s Peasants, in which elderly peasants who, after months of seeking justice in their village, decide to go to the township and county level to beg officials to intervene, only to be turned down. At one point, in a blatant reversal of cultural ethics, the elderly are described as kneeling in front of young government officials, who remain standing and ignore their pleas. Little did I know that a few days after reading this passage, Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) would practically behave like those young, callous officials after Taiwanese asked for help amid the devastation brought by Typhoon Morakot. In scene after scene, Ma has looked annoyed, impatient, and would often hide behind a wall of security officials as Taiwanese sought to approach him. On some occasions, elderly Taiwanese fell on their knees, and Ma remained standing, displaying a level of cultural insensitivity that will not be forgotten anytime soon. In that regard, Ma’s wife, first lady Chow Mei-ching (周美青), has fared much better, going down on her knees to bring comfort to grieving individuals and seeming far more at ease among ordinary people than her husband has.Ma once again apologized publicly on Sunday for his government’s slow response to Typhoon Morakot. With thousands still stranded and without food for more than a week — something that was avoidable, had rescue efforts commenced when they should have — international media are beginning to criticize a leader who had hitherto managed to deflect all criticism, even when police overreacted to demonstrations during Chinese envoy Chen Yunlin’s (陳雲林) visit to Taipei in November, when the government attacked freedom of expression, when the judiciary less than impartially handled the Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) trial and that of other DPP officials, or when his administration chose to ignore widespread public fears created by his cross-strait policies. So pointed has the criticism become that at some point Beijing could start proposing that Taipei simply isn’t competent enough to govern itself and therefore Beijing has a mission civilisatrice to help its “compatriots” in Taiwan “modernize” themselves, a view that would certainly find echoes in China’s invasion of “barbaric” Tibet. That specter becomes less implausible when media outlets begin comparing Ma’s behavior with that of Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao (溫家寶) after the Sichuan Earthquake.

Ma ‘shoulders all responsibility’

At last, it would appear that Ma is finally being presidential, as he told media that he would “shoulder all the responsibility” for his government’s slow response to the emergency. But here’s the fine print: Asked by CNN on Sunday to explain what he meant by “shouldering all responsibility,” Ma replied that he would determine what was wrong with the rescue system, correct problems and discipline officials in charge. Now that’s taking responsibility! Not my fault…

Between ‘great powers’

Meanwhile, the great power game over Taiwan is on. Agence France-Presse reported on Sunday that both the US and China have offered helicopters to help with rescue operations in southern Taiwan. The US has offered CH-53Es Super Stallions, the US military’s largest and heaviest helicopter, while Beijing has offered what is being touted as the world’s largest helicopters (btb Russian-made Mi-26 helicopters). If the US military is allowed to come to Taiwan — officers say they could be here as early as late on Sunday (with transport aircraft already here) — this would be the first time since 1979, when Washington severed diplomatic ties with Taipei, that US troops stepped on Taiwanese soil to deliver humanitarian assistance. Given, as I have discussed, the Ma administration’s fixation on cross-strait rapprochement with Beijing and Ma’s reluctance to harm that relationship no matter what, the symbolism of a US presence on Taiwanese soil would be tremendous. Even more controversial, but probably inevitable, would be the deployment of Chinese military helicopters and troops in Taiwan. Aside from the obvious PR value of Chinese soldiers bringing humanitarian assistance to Taiwanese, it would be the first time in history that the People’s Liberation Army puts boots on the ground in Taiwan, which Beijing claims as its own. The propaganda coup that this would serve both the Ma administration and the CCP would be immense and far-reaching.

Meanwhile, the great power game over Taiwan is on. Agence France-Presse reported on Sunday that both the US and China have offered helicopters to help with rescue operations in southern Taiwan. The US has offered CH-53Es Super Stallions, the US military’s largest and heaviest helicopter, while Beijing has offered what is being touted as the world’s largest helicopters (btb Russian-made Mi-26 helicopters). If the US military is allowed to come to Taiwan — officers say they could be here as early as late on Sunday (with transport aircraft already here) — this would be the first time since 1979, when Washington severed diplomatic ties with Taipei, that US troops stepped on Taiwanese soil to deliver humanitarian assistance. Given, as I have discussed, the Ma administration’s fixation on cross-strait rapprochement with Beijing and Ma’s reluctance to harm that relationship no matter what, the symbolism of a US presence on Taiwanese soil would be tremendous. Even more controversial, but probably inevitable, would be the deployment of Chinese military helicopters and troops in Taiwan. Aside from the obvious PR value of Chinese soldiers bringing humanitarian assistance to Taiwanese, it would be the first time in history that the People’s Liberation Army puts boots on the ground in Taiwan, which Beijing claims as its own. The propaganda coup that this would serve both the Ma administration and the CCP would be immense and far-reaching.As the Ma administration has given the go-ahead for a US presence in Taiwan, however, it will feel immense pressure to balance matters by also inviting/allowing the Chinese to do so. In fact, it is not impossible that during the so-called “temporary” refusal of foreign aid, Beijing and Taipei negotiated an arrangement behind the scenes by which Taipei could only request US assistance if it also requested it from China. Is should also be noted that refusing one or the other in this situation would have serious ramifications for future bilateral relations between Taiwan, China and the US, as well as between China and the US over “right of involvement” in the region.

Rarely has humanitarian aid had such complex political variables; what should be purely relief considerations has become politicized and may have created delays that, sadly, will cost lives. One could advance the argument that before Taiwan under Ma made Beijing its center of gravity, Taipei would have had far more flexibility in requesting foreign humanitarian assistance, or that before turning Beijing into a virtual decision-maker for Taipei, offers of assistance by Tokyo and Washington could have been accepted with far greater ease — and much earlier — regardless of whether Beijing liked it or not. The price of this shift may now have to be calculated in Taiwanese lives. Conversely, if Ma had not come to be seen, because of his pro-China policies, as a puppet of Beijing, he would have had more latitude in accepting aid from China, and the presence of Chinese soldiers on Taiwanese soil would not as readily been interpreted as capitulation on sovereignty.

Saturday, August 15, 2009

Did politics undermine rescue efforts in Taiwan?

Speculation has been rife in the past week that the Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) administration’s slow response to the catastrophic flooding in southern Taiwan following the passage of Typhoon Morakot on Aug. 8 was the result of ingrained indifference among pan-blue politicians for the welfare of predominantly green Taiwanese in the south. Others, meanwhile, have pointed not so much to domestic politics as to racism, whereby the lives of Han Chinese are deemed more important than those of native Taiwanese or Aborigines, who have born the brunt of the devastation.

Speculation has been rife in the past week that the Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) administration’s slow response to the catastrophic flooding in southern Taiwan following the passage of Typhoon Morakot on Aug. 8 was the result of ingrained indifference among pan-blue politicians for the welfare of predominantly green Taiwanese in the south. Others, meanwhile, have pointed not so much to domestic politics as to racism, whereby the lives of Han Chinese are deemed more important than those of native Taiwanese or Aborigines, who have born the brunt of the devastation.Although racism and deep-blue resentment for deep-green individuals may be an undercurrent in some individuals, it is hard to imagine that elected officials seeking reelection would willingly allow people to die because of such beliefs. It would be equally difficult to conceive of a top-down directive ordering relief workers and the military not to intervene because of the ethnicity of the victims.

Domestic, external variables

While we cannot rule out these variables to explain the belated response by the central government, two likelier causes for its failure to act in timely fashion are (a) government incompetence and (b) the Ma administration’s fixation with cross-strait relations. Feasibly, the central government’s failure to respond was a combination of both.

Symptoms of incompetence in the context of the Morakot disaster include a failure to understand the magnitude of the catastrophe; an apparent lack of coordination between the central authorities and local governments; a failure to deploy enough troops early enough; focus on money and reconstruction rather than immediate rescue contingencies; a failure to declare a state of emergency; buck-passing; and a lack of presidential involvement. Buck-passing especially supports the incompetence theory, such as when Ma said that the Central Weather Bureau was to blame for failing to predict the amount of rainfall Morakot would bring. When a government accuses an agency of failing to predict an imponderable and then blames that same agency for the slow government response once the facts on the ground are quantifiable, what it is doing is trying to deflect blame. Ma has also blamed local governments, many of which simply do not have the resources to deal with a catastrophe of such magnitude, and kept a safe distance by declaring that the Cabinet, rather than the president, should be in charge, which is another way to ensure that criticism will be directed at subordinates rather than himself.

Ma’s strategy, however, appears to be backfiring, and this is mostly the result of the external variable — that is, his fixation with Beijing, and people’s perception of his willingness to please the Chinese Communist Party. While it would be invidious to blame Ma for the failure of his entire government to react appropriately to the Morakot disaster, he nevertheless serves as the symbol of his administration, and how it acts will for the most part be a reflection of his political preferences — especially when Ma, both as president and soon-to-be Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chairman, wields such power over the executive and the legislature.

Ma’s tunnel vision, whereby everything becomes predicated on improving ties with Beijing, would readily explain the otherwise nonsensical directive from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) to all its missions abroad not to accept assistance. Once that memo was leaked to the media, MOFA officials rushed to claim that the directive was only “temporary,” without explaining why a temporary order — when help is immediately needed — would be any less damaging.

‘Angering’ Beijing

The Ma administration’s initial refusal of aid — especially much-needed materiel such as transport helicopters and humanitarian assistance expertise — could find its roots in Taipei’s fear of “angering” Beijing by opening its sovereignty to foreign countries, especially the US and Japan, which were the first to offer. Memories of the 921 Earthquake 10 years ago, when Beijing virtually hijacked international relief efforts by forcing aid to pass through China before entering Taiwan, must have weighed heavily in the Ma administration’s decision to turn down assistance. Rather than risk causing friction by immediately allowing foreign troops and humanitarian workers to come to Taiwan, the Ma government claimed help was unnecessary and that everything was under control. In other words, not alienating Beijing took precedence over saving lives.

The interplay of incompetence and the external factor of relations with Beijing meant that Taipei may have been willing to underestimate the severity of the disaster. Under different circumstances (paranoid leaderships like those in Myanmar and North Korea aside), a central government would have had no compunction in allowing foreign aid, even if this meant overshooting — i.e., receiving more aid than is required to meet immediate needs. For Taiwan, however, whose sovereign status is unrecognized by Beijing, overshooting was not an option, largely because of the political ramifications of receiving foreign assistance. The Ma administration therefore acted cautiously and underestimated the need, thus ensuring that Beijing would not be aggravated; at minimum, it gave Taipei time to negotiate with Chinese officials for “permission” to allow foreign assistance, which could explain the “temporary” nature of the MOFA directive, or the Ma administration’s volte-face by first turning down aid, only to request it a few days later.

This now raises the very important question: Who are Ma and his administration serving: the people who put them in office, or their masters back in Beijing. When external political considerations undermine what should be the priority of a government — that is, the safety and welfare of the people they represent — one should question the legitimacy of the relationship. If the external agent is so corrupting as to compel an elected government not to do anything in its power to save the lives of its people, the very desirability of that dyad becomes doubtable.

Morakot was an unprecedented disaster, one that no government could have fully prepared for. The disaster forces us to ask whether some places — especially those that are located in mudslide-prone areas — are perhaps unsuited for human settlement, just as are the coastal areas in the US that, year after year, get swallowed by the forces of nature. This notwithstanding, the central government in Taiwan shares a great deal of responsibility for failing to comprehend the severity of the situation, and this was either the result of incompetence, external political considerations, or both. Military personnel, many of whom were eager to help but were told to stay put because the order from above had not been given, should have been deployed earlier, and in larger numbers. Only eight days after the typhoon hit are we seeing deployments that are commensurate with the devastation in southern Taiwan. If, for some reason, troop mobilization early on was infeasible, central authorities should have immediately called for outside assistance, and when it was offered, they should not have turned it down. Lastly, by focusing on reconstruction money rather than immediate rescue efforts, Taipei showed that its priorities were misplaced. In fact, Taiwan has plenty of money, and even if its emergency funds were insufficient, it could easily have tapped into its foreign reserve, which is the third largest in the world.

It was inevitable that lives would be lost. But the expected body count — 123 confirmed dead, with hundreds unaccounted for and unlikely to still be alive after one week — didn’t have to be so high. Some of those lives will have been lost because of the Ma administration’s incompetence and external political calculations.

Young minds show sense of social responsibility

I was off today, but duty still called and I ended up interviewing a brilliant and articulate student from Taipei American School who spearheaded efforts to send humanitarian aid down south. What was striking about the young man was not only his sense of duty to his community, but also his long-term perspective, which is rare in young people. This piece appeared in the Taipei Times today:

On Wednesday, Chang convened 40 members of the student senate and launched an appeal to students and parents to help.

About 48 hours later, four truckloads, or about 600 boxes, of emergency material — blankets, sleeping bags, instant noodles, toiletries, sanitary equipment and scouring powder — had been gathered and was ready to be shipped south. All donations came from parents, the community and schools.

By 5pm yesterday, the 600 boxes were on their way to Kaohsiung American School, whose superintendent will personally take the donations to Namasiya Township (那瑪夏) , Kaohsiung County.

Donors ranged from small children bringing a couple of blankets or stuffed animals, to parents, who brought truckloads of items.

While the corporate sector did not participate in the TAS relief program, Chang told the Taipei Times that many TAS parents are in senior positions at big corporations, and many of them made sure that their firms donated toward relief efforts.

Chang said yesterday’s effort was just a short-term initiative, adding that plans are being made for TAS to foster schools destroyed in the south and help with reconstruction.

TAS has a long tradition of helping out in poor countries, Chang said.

“However, it’s not often that we get to help out at home,” he added.

Wednesday, August 12, 2009

As expected ... Beijing allegedly pledges US$16m

Agence France-Presse reported late this evening that China had pledged US$16 million for relief efforts following the devastation brought by Typhoon Morakot. If true, the donation would dwarf pledges of US$250,000 and US$103,000 by the US and Japan respectively. According to AFP, China’s financial assistance would come via the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Strait.

Agence France-Presse reported late this evening that China had pledged US$16 million for relief efforts following the devastation brought by Typhoon Morakot. If true, the donation would dwarf pledges of US$250,000 and US$103,000 by the US and Japan respectively. According to AFP, China’s financial assistance would come via the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Strait.It is no small irony that a country that threatens to invade its neighbor, or to attack it with short- and mid-range missiles, would suddenly turn into a generous humanitarian donor. While money is certainly welcome, this is not the result of Chinese “warmth” — this is PR, and an effort to win hearts and minds in Taiwan by giving money. Wouldn’t it be nice if, rather than give when a catastrophe hits, China stopped threatening Taiwan, so that parts of the US$10 billion or so Taipei spends annually on the military to protect itself from China could be dedicated to, say, strengthening infrastructure. (To put things in perspective: A single DF-15 short-range ballistic missile, out of the about 1,400 DF-11s and DF-15s that China aims at Taiwan [excluding medium-range missiles], costs approximately US$450,000. In other words, China’s humanitarian pledge to Taiwan represents a mere 35 missiles. )

Additionally, while money and planning will be needed for reconstruction, the central government’s current emphasis on that phase, at a time when hundreds, if not thousands, of people are still stranded or missing, is just wrong. At this writing, a mere 8,500 soldiers have been deployed to conduct rescue operations, which isn’t enough, given the amplitude of the devastation. In the wake of a catastrophe, time and materiel are of the essence, which is why Premier Liu Chao-shiuan’s (劉兆玄) contention that Taiwan does not need non-financial assistance from countries that have offered it — Japan, the US — is myopic. When lives are at stake, transport aircraft from neighboring countries (e.g., US helicopters based in Guam or Okinawa) should be given precedence. Only once all lives have been accounted for, and health hazards addressed, should we turn to reconstruction. By turning priorities upside down, the Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) administration is not only putting lives at risk, but it may also be attempting to detract attention from its less than stellar handling of the crisis.

When a house is burning, we should make sure everybody is out and safe before sitting down and discussing how to rebuild the roof or replace the furniture.

Tuesday, August 11, 2009

The cost of complicity