It seems that the campaign to oust Taiwanese President Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) is one of those things that just won’t go away until the deed has become reality. First, an attempt to recall the president failed in June, and for a while it seemed that Chen had weathered the storm. But starting in early September a continuous sit-in and a series of public demonstrations were held in cities throughout Taiwan—events which with but a few unfortunate exceptions were peaceful and orderly. And now it appears that a second recall vote is being considered.

What worries me isn’t the recall process or even the demonstrations, however circus-like they’ve become, what with the concerts held and merchants lining the streets. Though these fall outside the system of law whereby the Taiwanese head of state can be held to account, they are—or should be—intrinsically harmless. What makes me pause as I find myself on Zhong Hua avenue are the swarms of red: T-shirts, baseball caps and flags. Red, as we all know, has long been associated with communism, and the color has long had a special connotation here in Taiwan. It is therefore surprising that the so-called “alliance” against corruption—which in reality is against Chen, for if the people were to turn against corruption per se, most legislators, DPP or KMT, would be jobless as we speak. Whatever they tell the masses, the organizers have made this a crusade against one individual, and that individual is president Chen.

The theory that I am about to propose has already awakened the wrath of the principal organizer of the sit-ins, former DPP Chairman Shih Ming-teh (施明德), who threatened to sue a media outlet that hinted at the possibility that I am about to put on the table. Now, despite the obvious connotation of the color red, I would not establish a theory based on that alone, though I still find it interesting that the organizers of the anti-Chen campaign would choose it to represent their endeavors. They couldn’t use blue, surely, for fear that the whole thing would be perceived to be a pan-blue (that is, KMT-led) effort. Nor could it be green, a color that is associated with Chen’s DPP. But of all the colors remaining in the palette, why did Shih et al have to pick red?

The theory that I am about to propose has already awakened the wrath of the principal organizer of the sit-ins, former DPP Chairman Shih Ming-teh (施明德), who threatened to sue a media outlet that hinted at the possibility that I am about to put on the table. Now, despite the obvious connotation of the color red, I would not establish a theory based on that alone, though I still find it interesting that the organizers of the anti-Chen campaign would choose it to represent their endeavors. They couldn’t use blue, surely, for fear that the whole thing would be perceived to be a pan-blue (that is, KMT-led) effort. Nor could it be green, a color that is associated with Chen’s DPP. But of all the colors remaining in the palette, why did Shih et al have to pick red?Colors aside, my worries come from the literature on China’s tradition of meddling in Taiwanese affairs. “Taiwanese compatriots are our flesh and blood, we sincerely hope for a peaceful society in Taiwan where the economy develops and people live happily,” said the spokesman of the Taiwan Affairs Office, Li Weiyi (李維一), on Sept. 13. “Our stance and efforts to promote close cross-strait exchanges and all kinds of economic cooperation are unchanged.” At face value, this comment would seem to indicate that Beijing has taken a hands-off approach to recent developments in Taiwan. But then again, who can believe a state that increasingly is regulating the state-controlled media to such an extent as to make the lives of foreign news agencies a newsmaker’s nightmare? I take little comfort in a spokesman of the Taiwan Affairs Office telling us that Beijing wants “a peaceful society,” more so when in the same speech he feels the obligation to mention that China firmly opposes the separatist forces on the island.

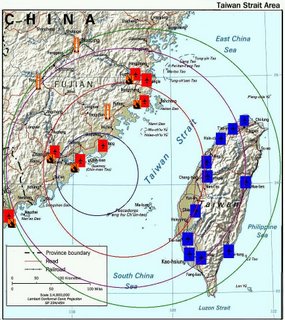

Therein lies the key to my theory: it is true that Beijing wants a Taiwan “where the economy develops and people live happily.” After all, who would want to reunite with a chaotic state with an economy in shambles? Despite the saber rattling, hundreds of short- and mid-range missiles pointing at Taiwan and almost weekly threats of invasion, very few are those within the Chinese Communist Party who honestly seek a military confrontation with Taipei. The reason is simple: whether it could actually win the war or not (which would depend on whether the US is capable of deploying rapidly enough to come to Taiwan’s aid), the economic consequences would be catastrophic for China. The CCP gets its legitimacy through the promise of economic prosperity in China; a war with Taiwan and the assured international embargo and sanctions against Beijing that would ensue—added to the freezing of economic activities between Hong Kong and Taiwan—would undermine that prosperity, the consequences of which could very well include the attempted overthrow of the regime in Beijing. And it is unlikely, too, that despite the sometimes irrational decisions that accompany a strong, emotional sense of nationalism, Beijing would overtly go to war with Taiwan and thereby risk losing the 2008 Olympic Games.

Therein lies the key to my theory: it is true that Beijing wants a Taiwan “where the economy develops and people live happily.” After all, who would want to reunite with a chaotic state with an economy in shambles? Despite the saber rattling, hundreds of short- and mid-range missiles pointing at Taiwan and almost weekly threats of invasion, very few are those within the Chinese Communist Party who honestly seek a military confrontation with Taipei. The reason is simple: whether it could actually win the war or not (which would depend on whether the US is capable of deploying rapidly enough to come to Taiwan’s aid), the economic consequences would be catastrophic for China. The CCP gets its legitimacy through the promise of economic prosperity in China; a war with Taiwan and the assured international embargo and sanctions against Beijing that would ensue—added to the freezing of economic activities between Hong Kong and Taiwan—would undermine that prosperity, the consequences of which could very well include the attempted overthrow of the regime in Beijing. And it is unlikely, too, that despite the sometimes irrational decisions that accompany a strong, emotional sense of nationalism, Beijing would overtly go to war with Taiwan and thereby risk losing the 2008 Olympic Games.Clearly, China stands to loose too much by engaging in military action against Taiwan. But there is nothing that prevents it from doing things covertly to “firmly oppose” the separatist forces on Taiwan—i.e. Chen. What if, somehow, certain elements in the anti-corruption campaign were being encouraged, if not supported, by Beijing? By this I do not mean that suitcases filled with money have necessarily found their way across the strait, but indirect support based on China’s desire for a Taiwan where the economy develops (remember, the KMT has long accused the DPP of not steering Taiwan’s economy well and has promised that, thanks to its close ties with China, it would do better on that aspect) is not altogether impossible. What if Beijing were underhandedly waging war against Taiwanese separatism by propping up the anti-corruption campaign, using it as a cover to accomplish one thing: the “peaceful” discrediting and eventual overthrow of the person who has made it his goal to rewrite the Taiwanese Constitution, change the county’s international status and obtain (so far unsuccessfully) a seat at the UN Security Council? What if this were yet another rung in Beijing’s attempts to isolate Taiwan diplomatically?

The literature on Beijing demanding that Taiwanese investors in China make a vow to oppose Taiwan independence, or on its buying information from retired Taiwanese military cadres is healthy, as are the CCP’s relations with the KMT, with which it engages in diplomacy and thereby sidelines the official—and elected—government in Taipei. Pro-KMT businesses throughout Taiwan (see “Colors Shown,” Sept. 2) have encouraged their employees to show their support for the anti-Chen campaign by asking for donations and giving leave time in exchange for their participation in the event. I have even heard stories of entire offices asking their employees to wear red at work. That there would be a coincidence of interests between the CCP, the KMT and certain business people here in Taiwan wouldn’t be all that surprising. Add to this a well-planned media campaign and a politically divided island, and the people will follow, wear their red T-shirts and baseball caps and brave the rainy weather to suddenly oppose something that has long existed on the island (and in China) and which certainly isn’t limited to the president (not to mention that the whole thing was sparked as a result of accusations not against Chen himself but rather against his son-in-law).

But behind all this, there might be more than meets the eye. What Taiwanese need to ask themselves is, who stands to gain most from Chen’s ouster? Taiwan, or China. There is much to be commended in people’s effort to combat corruption. But in this case, participants should look beyond the official line to see if there might not be some ulterior motive to the endeavor.

If the anti-Chen campaign comes through, Beijing might just have launched a successful decapitation operation without the use of force.