Taiwan's new "anti-terrorism" bill

The Taiwanese Cabinet last week submitted a revised "anti-terrorism" bill that should alarm every Taiwanese. Lacking a definition of what constitutes terrorism and with little oversight to ensure that intelligence and law-enforcement agencies do not overstep their responsibilities in a way that would infringe upon the rights and freedoms of individuals, the new act, if passed, would represent a grave step backwards for the nascent democracy.

Having experienced and participated in activities that could only have been launched in a system where oversight is lacking and consequently where undue infringements are deemed permissible, I felt compelled to write about the dangers the proposed bill represents to Taiwan. Visitors can view the full op-ed, published in the Monday, March 26 issue of the Taipei Times, by clicking here.

Monday, March 26, 2007

Thursday, March 15, 2007

Thursday Afternoon in Taipei

On of the perks of working as an editor for a newspaper is that my work schedule is from 15:30 until 22:00, which, provided I get up early enough, gives me plenty of time in the morning and early afternoon to accomplish what people abiding by more traditional schedules could never hope of doing. Another advantage is that as newspapers are also published on weekends, one’s “weekend” need not fall on Saturday and Sunday. In my case, “weekend” is Thursday and Friday.

One little indulgence I have developed in recent months is to go, mid-afternoon, to this place called in House, a lounge bar situated in the Xin-yi district, about a five minute walk from Taipei 101. Not only is in House one of my favorite lounges in Taipei, with excellent house music and a dreamy décor, but the fact that I am going there in the middle of the week before dinnertime certainly adds to the experience.

After you have been seated by one of the invariably good-looking, fashionable waitresses or waiters, you are handed a drinks menu to choose from which offers a nice variety, from wines to whiskeys to multiple cocktails. Comfortably seated in a leather sofa, with the not-too-loud mix playing round you and the faded pink and blue hues bathing you in a dreamy mood — to which we add hundreds of candles on tables, hanging from the ceiling and on windowsills — you place your order. From noon until 18:00, all drinks come with a cake or sorbet. What will it be, a 15-year-old single malt, or a kamikaze? Red wine, or a Mai Tai?

For me, part of the experience lies in the surrealism of it all. It’s as if reality were a dial and you shifted it, say, thirty degrees. There is something unreal about being in a lounge bar in mid-afternoon on a workday. It’s like stepping into a different world — not altogether unlike the real world, but like I said, a few degrees off. I also like to observe people there, for I never find myself alone in there. For me, I bring a book and read while I munch on peanuts, take a sip from my drink and eat my sorbet or cake. Others come in small groups. Some are hunched around a portable computer, talking shop, the bright monitor an out-of-place yet natural intrusion into the otherwise somber atmosphere. Others come alone, engrossed in a cigar, or deep in conversation on the ubiquitous cell phone. It’s amazing how many people one will find in a lounge at this time of the day. While some do conduct business there, for the majority it is, like me, leisure, a hedonistic escapade from reality. Looking at them, I always wonder what it is they do so that they can be there on a weekday. True, Taipei has more than its share of utterly rich people who need not have a day job for their entire lives. Maybe the people around me think I am one of them, who knows? I could very well see myself spending entire days there, writing a novel, perhaps.

At any time, it’s a place to see and be seen, where one drops all his worries and allows himself to be embraced by the alcohol and the enthralling lounge music. Make that a weekday experience, and the escapism is all the more complete.

On of the perks of working as an editor for a newspaper is that my work schedule is from 15:30 until 22:00, which, provided I get up early enough, gives me plenty of time in the morning and early afternoon to accomplish what people abiding by more traditional schedules could never hope of doing. Another advantage is that as newspapers are also published on weekends, one’s “weekend” need not fall on Saturday and Sunday. In my case, “weekend” is Thursday and Friday.

One little indulgence I have developed in recent months is to go, mid-afternoon, to this place called in House, a lounge bar situated in the Xin-yi district, about a five minute walk from Taipei 101. Not only is in House one of my favorite lounges in Taipei, with excellent house music and a dreamy décor, but the fact that I am going there in the middle of the week before dinnertime certainly adds to the experience.

After you have been seated by one of the invariably good-looking, fashionable waitresses or waiters, you are handed a drinks menu to choose from which offers a nice variety, from wines to whiskeys to multiple cocktails. Comfortably seated in a leather sofa, with the not-too-loud mix playing round you and the faded pink and blue hues bathing you in a dreamy mood — to which we add hundreds of candles on tables, hanging from the ceiling and on windowsills — you place your order. From noon until 18:00, all drinks come with a cake or sorbet. What will it be, a 15-year-old single malt, or a kamikaze? Red wine, or a Mai Tai?

For me, part of the experience lies in the surrealism of it all. It’s as if reality were a dial and you shifted it, say, thirty degrees. There is something unreal about being in a lounge bar in mid-afternoon on a workday. It’s like stepping into a different world — not altogether unlike the real world, but like I said, a few degrees off. I also like to observe people there, for I never find myself alone in there. For me, I bring a book and read while I munch on peanuts, take a sip from my drink and eat my sorbet or cake. Others come in small groups. Some are hunched around a portable computer, talking shop, the bright monitor an out-of-place yet natural intrusion into the otherwise somber atmosphere. Others come alone, engrossed in a cigar, or deep in conversation on the ubiquitous cell phone. It’s amazing how many people one will find in a lounge at this time of the day. While some do conduct business there, for the majority it is, like me, leisure, a hedonistic escapade from reality. Looking at them, I always wonder what it is they do so that they can be there on a weekday. True, Taipei has more than its share of utterly rich people who need not have a day job for their entire lives. Maybe the people around me think I am one of them, who knows? I could very well see myself spending entire days there, writing a novel, perhaps.

At any time, it’s a place to see and be seen, where one drops all his worries and allows himself to be embraced by the alcohol and the enthralling lounge music. Make that a weekday experience, and the escapism is all the more complete.

Tuesday, March 06, 2007

Empty Rhetoric in Politics

Diplomacy, it seems, is as much damage control as it is the substantial fashioning of relationships between states. The principal tool of diplomats — especially when it comes to damage control — is, obviously, rhetoric. By paying close attention to what is being said, it is easy to determine whether a state has a well-rounded, coherent strategy or is just struggling to maintain the appearance of having a handle on things. As we saw last week with US Vice-President Dick Cheney’s threats to Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf on the issue of fighting the Taliban, contradiction are usually indicative of policymaking confusion.

This week, Washington once more proved that its policies on the Taiwan Strait issue is no more coherent. The first instance is actually a long continuation of a trend, which consists of (a) a paranoid view of Chinese military growth (the People’s Republic of China’s military budget increased 17.8 percent this year) and the incessant references to the “threat” that this poses to neighboring states and US interests in the region; and (b) of Washington’s recriminatory attitude whenever Taiwanese President Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) makes any kind of reference to independence, which Washington never fails to slap down as a “threat to peace and security in the Taiwan Strait” and as threatening to US support for the democratic nation. Here again, the contradiction is a lurid one: non-democratic, expansionist China is a growing threat, democratic Taiwan is an ally worthy of protection, but any attempt at normalization of status or reference to independence in face of Beijing’s avowed threats of military aggression is portrayed as treason.

This week, Washington once more proved that its policies on the Taiwan Strait issue is no more coherent. The first instance is actually a long continuation of a trend, which consists of (a) a paranoid view of Chinese military growth (the People’s Republic of China’s military budget increased 17.8 percent this year) and the incessant references to the “threat” that this poses to neighboring states and US interests in the region; and (b) of Washington’s recriminatory attitude whenever Taiwanese President Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) makes any kind of reference to independence, which Washington never fails to slap down as a “threat to peace and security in the Taiwan Strait” and as threatening to US support for the democratic nation. Here again, the contradiction is a lurid one: non-democratic, expansionist China is a growing threat, democratic Taiwan is an ally worthy of protection, but any attempt at normalization of status or reference to independence in face of Beijing’s avowed threats of military aggression is portrayed as treason.

The reason why Washington’s rhetoric is so contradictory is that its policy on Taiwan is actually a non-policy — the maintenance, in lieu of progress, of the status quo whereby China will not invade Taiwan and the latter will not declare unilateral independence. It would be all nice well if the international system were static and the balance of power unchanging, but that is not the case. Beijing is building up and modernizing its military, and there are growing indications that Beijing may not always have full control of its military apparatus, which one day could result in enterprising individuals making military decisions that do not entirely correspond to or reflect the wishes of the civilian leadership. While the panicking, to the point of irrationality, segments of the US intelligentsia and policymaking circles overestimate the Chinese “threat” and misrepresent its aims and intentions, it remains that Beijing’s policy on Taiwan does include the use of force — and the odd 1,000 missiles it points at Taiwan as well as the language adopted in its “Anti-Secession” Act attest to that. With these two contradictory forces shaping Washington’s views, its language becomes one of obfuscation, one that simply cannot lead to political development.

Taiwan is therefore a friend, in extremis one worthy of protection, but it cannot be allowed to act in its own interest or to seek for its 23 million people the representation on the world stage that they deserve. Beijing, for its part, is at times friend, at times enemy, a partner in trade but a brewing storm over the horizon. The signals are mixed, and diplomats’ rhetoric reflects that.

Aside from contradictory language, empty, meaningless rhetoric is also part of the diplomat’s toolbox. Something needs to be said to fill a void, but once it is analyzed it is obvious that whatever was said makes no contribution whatsoever. The Taiwan Strait conflict offers many examples of this, such as when US Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte, visiting China over the weekend, said that the 450 air-ground missiles the US intends to sell Taiwan to equip its F16s “would be for strictly defensive purposes and consistent with our ‘one China’ policy.” Close scrutiny of the language cannot but beg the question: what other use but a defensive one would Taiwan make of these missiles — invade China, perhaps? Everybody and their dog knows that the only reason why Taipei would seek such weapons, along with other packages, is to defend itself from an eventual military attack by China (whether a successful defense, under the present conditions, can be achieved is beyond the scope of this entry).

One would think that clear, rational policies lie behind and inform the relations between states — more so when it comes to unstable issues like Taiwan and China. The reality, however, is otherwise. Look to the language, see what is being said. More often than one would think, the rhetoric is empty and the diplomat is no more than the messenger attempting to buy time.

Diplomacy, it seems, is as much damage control as it is the substantial fashioning of relationships between states. The principal tool of diplomats — especially when it comes to damage control — is, obviously, rhetoric. By paying close attention to what is being said, it is easy to determine whether a state has a well-rounded, coherent strategy or is just struggling to maintain the appearance of having a handle on things. As we saw last week with US Vice-President Dick Cheney’s threats to Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf on the issue of fighting the Taliban, contradiction are usually indicative of policymaking confusion.

This week, Washington once more proved that its policies on the Taiwan Strait issue is no more coherent. The first instance is actually a long continuation of a trend, which consists of (a) a paranoid view of Chinese military growth (the People’s Republic of China’s military budget increased 17.8 percent this year) and the incessant references to the “threat” that this poses to neighboring states and US interests in the region; and (b) of Washington’s recriminatory attitude whenever Taiwanese President Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) makes any kind of reference to independence, which Washington never fails to slap down as a “threat to peace and security in the Taiwan Strait” and as threatening to US support for the democratic nation. Here again, the contradiction is a lurid one: non-democratic, expansionist China is a growing threat, democratic Taiwan is an ally worthy of protection, but any attempt at normalization of status or reference to independence in face of Beijing’s avowed threats of military aggression is portrayed as treason.

This week, Washington once more proved that its policies on the Taiwan Strait issue is no more coherent. The first instance is actually a long continuation of a trend, which consists of (a) a paranoid view of Chinese military growth (the People’s Republic of China’s military budget increased 17.8 percent this year) and the incessant references to the “threat” that this poses to neighboring states and US interests in the region; and (b) of Washington’s recriminatory attitude whenever Taiwanese President Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) makes any kind of reference to independence, which Washington never fails to slap down as a “threat to peace and security in the Taiwan Strait” and as threatening to US support for the democratic nation. Here again, the contradiction is a lurid one: non-democratic, expansionist China is a growing threat, democratic Taiwan is an ally worthy of protection, but any attempt at normalization of status or reference to independence in face of Beijing’s avowed threats of military aggression is portrayed as treason.The reason why Washington’s rhetoric is so contradictory is that its policy on Taiwan is actually a non-policy — the maintenance, in lieu of progress, of the status quo whereby China will not invade Taiwan and the latter will not declare unilateral independence. It would be all nice well if the international system were static and the balance of power unchanging, but that is not the case. Beijing is building up and modernizing its military, and there are growing indications that Beijing may not always have full control of its military apparatus, which one day could result in enterprising individuals making military decisions that do not entirely correspond to or reflect the wishes of the civilian leadership. While the panicking, to the point of irrationality, segments of the US intelligentsia and policymaking circles overestimate the Chinese “threat” and misrepresent its aims and intentions, it remains that Beijing’s policy on Taiwan does include the use of force — and the odd 1,000 missiles it points at Taiwan as well as the language adopted in its “Anti-Secession” Act attest to that. With these two contradictory forces shaping Washington’s views, its language becomes one of obfuscation, one that simply cannot lead to political development.

Taiwan is therefore a friend, in extremis one worthy of protection, but it cannot be allowed to act in its own interest or to seek for its 23 million people the representation on the world stage that they deserve. Beijing, for its part, is at times friend, at times enemy, a partner in trade but a brewing storm over the horizon. The signals are mixed, and diplomats’ rhetoric reflects that.

Aside from contradictory language, empty, meaningless rhetoric is also part of the diplomat’s toolbox. Something needs to be said to fill a void, but once it is analyzed it is obvious that whatever was said makes no contribution whatsoever. The Taiwan Strait conflict offers many examples of this, such as when US Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte, visiting China over the weekend, said that the 450 air-ground missiles the US intends to sell Taiwan to equip its F16s “would be for strictly defensive purposes and consistent with our ‘one China’ policy.” Close scrutiny of the language cannot but beg the question: what other use but a defensive one would Taiwan make of these missiles — invade China, perhaps? Everybody and their dog knows that the only reason why Taipei would seek such weapons, along with other packages, is to defend itself from an eventual military attack by China (whether a successful defense, under the present conditions, can be achieved is beyond the scope of this entry).

One would think that clear, rational policies lie behind and inform the relations between states — more so when it comes to unstable issues like Taiwan and China. The reality, however, is otherwise. Look to the language, see what is being said. More often than one would think, the rhetoric is empty and the diplomat is no more than the messenger attempting to buy time.

Wednesday, February 28, 2007

Remembering the 228 Incident

Sixty years ago, on Feb. 28, 1947, began what would lead to the slaughter of between 20,000 and 30,000 Taiwanese during a security crackdown by Republic of China officers. The event, which ostensibly was sparked the previous day by a dispute between a cigarette vendor and an anti-smuggling officer, quickly turned into a days-long civil disorder and open rebellion against the corruption and illegitimacy of the regime that, since the handover by former colonial occupier Japan in 1945, had imposed its rule on the island. The distant Kuomintang (KMT) regime on the mainland soon sent reinforcements and in the ensuing days its officers launched in sometimes random, sometimes systematic killings. An American visiting at the time reported beheadings and rapes. The incident, for which recently released accounts now put the blame on Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), opened the door to the White Terror era, which lasted until 1987 and during which tens of thousands of Taiwanese were disappeared, imprisoned or killed.

Sixty years ago, on Feb. 28, 1947, began what would lead to the slaughter of between 20,000 and 30,000 Taiwanese during a security crackdown by Republic of China officers. The event, which ostensibly was sparked the previous day by a dispute between a cigarette vendor and an anti-smuggling officer, quickly turned into a days-long civil disorder and open rebellion against the corruption and illegitimacy of the regime that, since the handover by former colonial occupier Japan in 1945, had imposed its rule on the island. The distant Kuomintang (KMT) regime on the mainland soon sent reinforcements and in the ensuing days its officers launched in sometimes random, sometimes systematic killings. An American visiting at the time reported beheadings and rapes. The incident, for which recently released accounts now put the blame on Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), opened the door to the White Terror era, which lasted until 1987 and during which tens of thousands of Taiwanese were disappeared, imprisoned or killed.

As I write this, commemorative ceremonies throughout Taiwan are being held. Just outside the window, a procession is snaking its way through the streets of the neighborhood, loud gongs and cymbals and various wind instruments, accentuated by powerful firecrackers, paraphrasing the screams of those who fell sixty years ago.

Taiwan probably wouldn’t be what it is today without its own terrible formative incidents, of which 228 was, sadly, but one among many. Nor would it be the democracy it is today had it not been for KMT rule, however repressive it might have been. The fact is, nations must build upon the geography and history they are dealt and make the most of it. And 228, painful as the memories are, is part of that dowry. It is important that these events be remembered, dug up, and studied, that attempts to comprehend them be sustained and that future generations be taught them, as they constitute the very DNA of a people. By dealing with those memories in a peaceful — perhaps even forgiving manner — Taiwanese, as have other nations that have come to accept their violent past, can serve as an example to peoples who are currently experiencing political violence or will do so in future.

Sixty years ago, on Feb. 28, 1947, began what would lead to the slaughter of between 20,000 and 30,000 Taiwanese during a security crackdown by Republic of China officers. The event, which ostensibly was sparked the previous day by a dispute between a cigarette vendor and an anti-smuggling officer, quickly turned into a days-long civil disorder and open rebellion against the corruption and illegitimacy of the regime that, since the handover by former colonial occupier Japan in 1945, had imposed its rule on the island. The distant Kuomintang (KMT) regime on the mainland soon sent reinforcements and in the ensuing days its officers launched in sometimes random, sometimes systematic killings. An American visiting at the time reported beheadings and rapes. The incident, for which recently released accounts now put the blame on Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), opened the door to the White Terror era, which lasted until 1987 and during which tens of thousands of Taiwanese were disappeared, imprisoned or killed.

Sixty years ago, on Feb. 28, 1947, began what would lead to the slaughter of between 20,000 and 30,000 Taiwanese during a security crackdown by Republic of China officers. The event, which ostensibly was sparked the previous day by a dispute between a cigarette vendor and an anti-smuggling officer, quickly turned into a days-long civil disorder and open rebellion against the corruption and illegitimacy of the regime that, since the handover by former colonial occupier Japan in 1945, had imposed its rule on the island. The distant Kuomintang (KMT) regime on the mainland soon sent reinforcements and in the ensuing days its officers launched in sometimes random, sometimes systematic killings. An American visiting at the time reported beheadings and rapes. The incident, for which recently released accounts now put the blame on Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), opened the door to the White Terror era, which lasted until 1987 and during which tens of thousands of Taiwanese were disappeared, imprisoned or killed.As I write this, commemorative ceremonies throughout Taiwan are being held. Just outside the window, a procession is snaking its way through the streets of the neighborhood, loud gongs and cymbals and various wind instruments, accentuated by powerful firecrackers, paraphrasing the screams of those who fell sixty years ago.

Taiwan probably wouldn’t be what it is today without its own terrible formative incidents, of which 228 was, sadly, but one among many. Nor would it be the democracy it is today had it not been for KMT rule, however repressive it might have been. The fact is, nations must build upon the geography and history they are dealt and make the most of it. And 228, painful as the memories are, is part of that dowry. It is important that these events be remembered, dug up, and studied, that attempts to comprehend them be sustained and that future generations be taught them, as they constitute the very DNA of a people. By dealing with those memories in a peaceful — perhaps even forgiving manner — Taiwanese, as have other nations that have come to accept their violent past, can serve as an example to peoples who are currently experiencing political violence or will do so in future.

Signs of failure

Despite US President George W. Bush’s constant declarations to the effect that al-Qaeda has been weakened by the “war on terrorism” launched in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, analysts the world over are now revisiting this assumption (see “How not to win,” Feb. 26).

A clear indication of this failure to eliminate the threat can be found in recent comments by no less a player in antiterrorism than Dame Eliza Manningham-Buller, the head of the British domestic intelligence service, MI5. In November, Manningham-Buller — well-known for her usually less alarmist assessments of the terrorist threat than those of the government she serves — said that since 2005 MI5 had identified 30 major terrorist plots in Britain and was monitoring the activities of — take a deep breath — no less than 1,600 Britain-based individuals from approximately 200 terrorist networks. This is on the home front alone! The exact same figures were repeated by London Metropolitan Police Deputy Commissioner Paul Stephenson at a security conference in Sydney, Australia, on Monday.

A clear indication of this failure to eliminate the threat can be found in recent comments by no less a player in antiterrorism than Dame Eliza Manningham-Buller, the head of the British domestic intelligence service, MI5. In November, Manningham-Buller — well-known for her usually less alarmist assessments of the terrorist threat than those of the government she serves — said that since 2005 MI5 had identified 30 major terrorist plots in Britain and was monitoring the activities of — take a deep breath — no less than 1,600 Britain-based individuals from approximately 200 terrorist networks. This is on the home front alone! The exact same figures were repeated by London Metropolitan Police Deputy Commissioner Paul Stephenson at a security conference in Sydney, Australia, on Monday.

With the population of Great Britain established at 60.7 million as of late last year, this means that there is one terrorist suspect for every 38,000 British — an astounding figure. Such a ratio would mean that Canada, with a population of 33 million, has 868 terrorists in its midst. If this were the case, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service would have to grow something like eight-fold so that it could monitor the activities of all those suspects. And this is excludes all the other usual groups targeted by intelligence services — the usual suspects, if you will — such as China, Russia, Iran and others. Given, based on my experiences, the usual ratio (and I am being very conservative here) of 2 intelligence officers for every target of an investigation, this would mean that in Canada, more than 1,700 intelligence officers would be working on the al-Qaeda file, a figure that excludes the communication intercepts specialists, translators, and other operational staff, not to mention pay and administrative staff, lawyers, and so on. (As of last year, the total workforce at CSIS, including administration, pay services and others, was approximately 2,400.)

But what those numbers truly show is that if they are true, the West is clearly doing something wrong, so wrong, in fact, that defeat in its “war on terrorism” is almost a fait accompli. Ever since they launched the campaign against al-Qaeda and other like-minded groups in 2001, the architects of the “war on terror” have repeatedly said that this new war is as much a military campaign as it is a war for the hearts and minds of people in the Muslim world. Given the MI5 numbers, it would appear that the hearts and minds part has either gone terribly wrong — or worse, that the leadership didn’t mean what it said. This, of course, is not entirely impossible, as to this day British Prime Minister Tony Blair still refuses to acknowledge that Britain’s actions in Iraq and Afghanistan have absolutely no impact upon domestic security.

The most alarming part is that even if the figures are most likely overblown, the intelligence community and the British government believe they are true, and they don’t seem to grasp that they are indicative of a monumental failure on the diplomatic and hearts and minds front. Absent such an understanding, such figures — real or inflated — can only but go up.

Despite US President George W. Bush’s constant declarations to the effect that al-Qaeda has been weakened by the “war on terrorism” launched in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, analysts the world over are now revisiting this assumption (see “How not to win,” Feb. 26).

A clear indication of this failure to eliminate the threat can be found in recent comments by no less a player in antiterrorism than Dame Eliza Manningham-Buller, the head of the British domestic intelligence service, MI5. In November, Manningham-Buller — well-known for her usually less alarmist assessments of the terrorist threat than those of the government she serves — said that since 2005 MI5 had identified 30 major terrorist plots in Britain and was monitoring the activities of — take a deep breath — no less than 1,600 Britain-based individuals from approximately 200 terrorist networks. This is on the home front alone! The exact same figures were repeated by London Metropolitan Police Deputy Commissioner Paul Stephenson at a security conference in Sydney, Australia, on Monday.

A clear indication of this failure to eliminate the threat can be found in recent comments by no less a player in antiterrorism than Dame Eliza Manningham-Buller, the head of the British domestic intelligence service, MI5. In November, Manningham-Buller — well-known for her usually less alarmist assessments of the terrorist threat than those of the government she serves — said that since 2005 MI5 had identified 30 major terrorist plots in Britain and was monitoring the activities of — take a deep breath — no less than 1,600 Britain-based individuals from approximately 200 terrorist networks. This is on the home front alone! The exact same figures were repeated by London Metropolitan Police Deputy Commissioner Paul Stephenson at a security conference in Sydney, Australia, on Monday.With the population of Great Britain established at 60.7 million as of late last year, this means that there is one terrorist suspect for every 38,000 British — an astounding figure. Such a ratio would mean that Canada, with a population of 33 million, has 868 terrorists in its midst. If this were the case, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service would have to grow something like eight-fold so that it could monitor the activities of all those suspects. And this is excludes all the other usual groups targeted by intelligence services — the usual suspects, if you will — such as China, Russia, Iran and others. Given, based on my experiences, the usual ratio (and I am being very conservative here) of 2 intelligence officers for every target of an investigation, this would mean that in Canada, more than 1,700 intelligence officers would be working on the al-Qaeda file, a figure that excludes the communication intercepts specialists, translators, and other operational staff, not to mention pay and administrative staff, lawyers, and so on. (As of last year, the total workforce at CSIS, including administration, pay services and others, was approximately 2,400.)

But what those numbers truly show is that if they are true, the West is clearly doing something wrong, so wrong, in fact, that defeat in its “war on terrorism” is almost a fait accompli. Ever since they launched the campaign against al-Qaeda and other like-minded groups in 2001, the architects of the “war on terror” have repeatedly said that this new war is as much a military campaign as it is a war for the hearts and minds of people in the Muslim world. Given the MI5 numbers, it would appear that the hearts and minds part has either gone terribly wrong — or worse, that the leadership didn’t mean what it said. This, of course, is not entirely impossible, as to this day British Prime Minister Tony Blair still refuses to acknowledge that Britain’s actions in Iraq and Afghanistan have absolutely no impact upon domestic security.

The most alarming part is that even if the figures are most likely overblown, the intelligence community and the British government believe they are true, and they don’t seem to grasp that they are indicative of a monumental failure on the diplomatic and hearts and minds front. Absent such an understanding, such figures — real or inflated — can only but go up.

Tuesday, February 27, 2007

How not to win

Amid rising fears — as it does every year around this time — of a new Taliban “spring offensive” against NATO troops in Afghanistan and rising concerns that al-Qaeda, to quote Condoleezza Rice’s odd wording, “has tried to regenerate some of its leadership” and may, as some so-called security experts would have us think, be planning future attacks, here comes US Vice President Dick Cheney, originally bound for meetings with the Afghan proconsul Hamid Karzai but barred from reaching Afghanistan — not by the Taliban, or terrorists, but rather by snow. Cheney therefore makes a secret stop in Pakistan and holds a lunch meeting with President Pervez Musharraf.

Amid rising fears — as it does every year around this time — of a new Taliban “spring offensive” against NATO troops in Afghanistan and rising concerns that al-Qaeda, to quote Condoleezza Rice’s odd wording, “has tried to regenerate some of its leadership” and may, as some so-called security experts would have us think, be planning future attacks, here comes US Vice President Dick Cheney, originally bound for meetings with the Afghan proconsul Hamid Karzai but barred from reaching Afghanistan — not by the Taliban, or terrorists, but rather by snow. Cheney therefore makes a secret stop in Pakistan and holds a lunch meeting with President Pervez Musharraf.

The symptoms of incoming defeat often lie in the things that are said by politicians and their spokespersons. For a few years now, the lies and contradictions coming out of the US military leadership in Iraq and in Washington when it talks about Iraq, have served as signal posts indicating the way ahead, and we all know what the road looks like. Because of the sheer amplitude of the Iraq fiasco, which now threatens to inflame an entire region, Afghanistan and even al-Qaeda have been taken off the front page. In fact, as Bruce Hoffman, professor at Georgetown University, puts it: “it appears that Iraq blinded us to the possibility of an al-Qaeda renaissance. The United States’ entanglement there has consumed the attention and resources of our country’s military and intelligence communities — at precisely the time that Osama bin Laden and other senior al-Qaeda commanders were in their most desperate straits and stood to benefit most from this distraction.”

So five years on, not only has the world’s most powerful military, with the support of some NATO countries, failed to destroy al-Qaeda, but it has in fact allowed it to regroup. Rather than take the blame for its incapacity to focus on the task at hand — i.e., “defeating” al-Qaeda following the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks — and to admit that its adventure in Iraq was misguided at best, Washington is resorting to the age-old dirty trick of shifting the blame. Every now and then, it lambastes its servants at NATO and tells them to do more in Afghanistan, to deploy more troops, to be more aggressive in their pursuit of the Taliban.

More recently, however, the Bush administration has turned the screw on the Pakistani government, which it wants to be more aggressive in its hunt for al-Qaeda. Reports of varying credibility claim that many insurgents attacking Coalition forces in Afghanistan use Pakistan — more specifically the Waziristan area — as a base. Musharraf’s statement that Pakistan “has done the maximum in the fight against terrorism,” was insufficient to prevent finger-pointing in Washington. “The Pakistanis remain committed to doing everything possible to fight al-Qaeda, but having said that, we also know that there's a lot more that needs to be done,” said the ever-Orwellian presidential spokesman Tony Snow. US administration officials now say that if Pakistan, despite the fact that it has done the “maximum” it can, fails to combat al-Qaeda and the Taliban in the so-called “tribal areas” (note the use of language to describe the area where the insurgents allegedly find haven, giving its people an aura of savageness not unlike that which has been used throughout history to characterize groups that needed to be civilized, or altogether eradicated) more aggressively, Washington’s military aid to Pakistan could be cut. In other words, Pakistan would need to receive certification, from no less a figure than George W. Bush, that it is doing all it can to fight al-Qaeda. Since what this imposes on Pakistan is hardly achievable (after all, it’s not like the US has itself been successful at combating insurgencies), we can easily predict that Islamabad would get a failing grade.

One wonders, however, what could be accomplished by this. This is a perfect example of the signals mentioned above, the signs that matters are spiraling out of Washington’s control. The language piles into contradictions. If it were to follow upon its threat to Pakistan, Washington would weaken it military at a time when it asks it to do more. Run faster or else I’ll stop giving you water. Stop giving the marathoner water and he is sure not to complete the race.

What the planners in Washington fail to understand is that its Manichean view of the war on terrorism — the “us against them” or “good versus evil” attitude it has adopted since 9/11 — is the wrong template for a country like Pakistan that is being compelled to wage war against its own people. Things on the ground are not black and white, and not all inhabitants in the “tribal” area are pro-Taliban or al-Qaeda supporters. But Bush, Cheney and their advisers fail to see that, or simply don’t care. The only sure way Musharraf could accomplish what Washington demands of him would be by razing northern Waziristan to the ground, something even Musharraf cannot bring himself to do. Effectively, what Washington is asking the Pakistani president to do is the very same type of action it exploited to demonize a recently hanged dictator — localized ethnocide. But even if Musharraf didn't go to that extent, he must always gauge the reaction of Pakistanis to what he does. In other words, he muct make domestic political calculations.

So Pakistan is stuck in a corner, and the fault is Washington’s. The Taliban spring offensive will come, as it does every year, and al-Qaeda will continue to regroup. Unable to focus on one thing, Washington will continue to do what it does best: call upon its proxies in the region and within NATO to do more, criticize them for not doing enough, and turn its attention elsewhere.

In Iran, perhaps?

Amid rising fears — as it does every year around this time — of a new Taliban “spring offensive” against NATO troops in Afghanistan and rising concerns that al-Qaeda, to quote Condoleezza Rice’s odd wording, “has tried to regenerate some of its leadership” and may, as some so-called security experts would have us think, be planning future attacks, here comes US Vice President Dick Cheney, originally bound for meetings with the Afghan proconsul Hamid Karzai but barred from reaching Afghanistan — not by the Taliban, or terrorists, but rather by snow. Cheney therefore makes a secret stop in Pakistan and holds a lunch meeting with President Pervez Musharraf.

Amid rising fears — as it does every year around this time — of a new Taliban “spring offensive” against NATO troops in Afghanistan and rising concerns that al-Qaeda, to quote Condoleezza Rice’s odd wording, “has tried to regenerate some of its leadership” and may, as some so-called security experts would have us think, be planning future attacks, here comes US Vice President Dick Cheney, originally bound for meetings with the Afghan proconsul Hamid Karzai but barred from reaching Afghanistan — not by the Taliban, or terrorists, but rather by snow. Cheney therefore makes a secret stop in Pakistan and holds a lunch meeting with President Pervez Musharraf.The symptoms of incoming defeat often lie in the things that are said by politicians and their spokespersons. For a few years now, the lies and contradictions coming out of the US military leadership in Iraq and in Washington when it talks about Iraq, have served as signal posts indicating the way ahead, and we all know what the road looks like. Because of the sheer amplitude of the Iraq fiasco, which now threatens to inflame an entire region, Afghanistan and even al-Qaeda have been taken off the front page. In fact, as Bruce Hoffman, professor at Georgetown University, puts it: “it appears that Iraq blinded us to the possibility of an al-Qaeda renaissance. The United States’ entanglement there has consumed the attention and resources of our country’s military and intelligence communities — at precisely the time that Osama bin Laden and other senior al-Qaeda commanders were in their most desperate straits and stood to benefit most from this distraction.”

So five years on, not only has the world’s most powerful military, with the support of some NATO countries, failed to destroy al-Qaeda, but it has in fact allowed it to regroup. Rather than take the blame for its incapacity to focus on the task at hand — i.e., “defeating” al-Qaeda following the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks — and to admit that its adventure in Iraq was misguided at best, Washington is resorting to the age-old dirty trick of shifting the blame. Every now and then, it lambastes its servants at NATO and tells them to do more in Afghanistan, to deploy more troops, to be more aggressive in their pursuit of the Taliban.

More recently, however, the Bush administration has turned the screw on the Pakistani government, which it wants to be more aggressive in its hunt for al-Qaeda. Reports of varying credibility claim that many insurgents attacking Coalition forces in Afghanistan use Pakistan — more specifically the Waziristan area — as a base. Musharraf’s statement that Pakistan “has done the maximum in the fight against terrorism,” was insufficient to prevent finger-pointing in Washington. “The Pakistanis remain committed to doing everything possible to fight al-Qaeda, but having said that, we also know that there's a lot more that needs to be done,” said the ever-Orwellian presidential spokesman Tony Snow. US administration officials now say that if Pakistan, despite the fact that it has done the “maximum” it can, fails to combat al-Qaeda and the Taliban in the so-called “tribal areas” (note the use of language to describe the area where the insurgents allegedly find haven, giving its people an aura of savageness not unlike that which has been used throughout history to characterize groups that needed to be civilized, or altogether eradicated) more aggressively, Washington’s military aid to Pakistan could be cut. In other words, Pakistan would need to receive certification, from no less a figure than George W. Bush, that it is doing all it can to fight al-Qaeda. Since what this imposes on Pakistan is hardly achievable (after all, it’s not like the US has itself been successful at combating insurgencies), we can easily predict that Islamabad would get a failing grade.

One wonders, however, what could be accomplished by this. This is a perfect example of the signals mentioned above, the signs that matters are spiraling out of Washington’s control. The language piles into contradictions. If it were to follow upon its threat to Pakistan, Washington would weaken it military at a time when it asks it to do more. Run faster or else I’ll stop giving you water. Stop giving the marathoner water and he is sure not to complete the race.

What the planners in Washington fail to understand is that its Manichean view of the war on terrorism — the “us against them” or “good versus evil” attitude it has adopted since 9/11 — is the wrong template for a country like Pakistan that is being compelled to wage war against its own people. Things on the ground are not black and white, and not all inhabitants in the “tribal” area are pro-Taliban or al-Qaeda supporters. But Bush, Cheney and their advisers fail to see that, or simply don’t care. The only sure way Musharraf could accomplish what Washington demands of him would be by razing northern Waziristan to the ground, something even Musharraf cannot bring himself to do. Effectively, what Washington is asking the Pakistani president to do is the very same type of action it exploited to demonize a recently hanged dictator — localized ethnocide. But even if Musharraf didn't go to that extent, he must always gauge the reaction of Pakistanis to what he does. In other words, he muct make domestic political calculations.

So Pakistan is stuck in a corner, and the fault is Washington’s. The Taliban spring offensive will come, as it does every year, and al-Qaeda will continue to regroup. Unable to focus on one thing, Washington will continue to do what it does best: call upon its proxies in the region and within NATO to do more, criticize them for not doing enough, and turn its attention elsewhere.

In Iran, perhaps?

Monday, February 26, 2007

A sound signal, with a caveat

The ruling last week by the Supreme Court of Canada that the antiterrorism provision allowing the authorities to detain indefinitely suspected terrorists was counter to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms — coming less than a month after Maher Arar received an official apology and a $11.5 million compensation from the Canadian government for its role in his deportation to Syria in 2002, where he was tortured — sends an encouraging signal to the world that Canada is in remission and that it recognizes, however belatedly, that some of the things it has done in the name of security have breached its age-old contract with its citizens.

At the heart of the issue are the Security Certificates which, under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), are emitted against foreign nationals or permanent residents suspected of terrorism. The certificates allow for the detention, without a fair judicial process, of those individuals for extended periods of time, pending deportation. Ostensibly to protect intelligence sources (usually foreign) and methods of collection, the accused and their defense lawyers are given no access to the charges against them or the intelligence used to back those charges, making a proper defense in the court of law virtually impossible. It is a system that, not altogether unfairly, has prompted comparisons to the manner in which the US has treated its prisoners in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

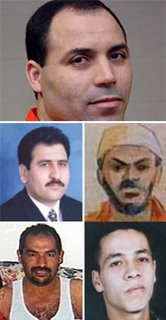

Eight cases are pending, and twenty have been resolved since 1991. Of the latter, 15 were deported. Of the 28 individuals, nineteen were of Arabic, Northern African or Persian origin. Unfortunately for the individuals whose cases are pending, the court suspended the ruling for a year to allow for a rewriting of the relevant parts of IRPA. The three most prominent cases — Hassan Almrei, Mohammed Zeki Mahjoub and Mahmoud Jaballah — this means a continuation of detentions that started in 2001, 2000 and 2001, respectively. Pictures: Mohamed Harkat (Algeria) released on bail in June 2006; clockwise from centre left: Hassan Almrei (Syria), Mohammed Mahjoub (Egypt), Mahmoud Jaballah (Egypt) and Adil Charkaoui (Morocco), freed on conditional release in February 2005.

Eight cases are pending, and twenty have been resolved since 1991. Of the latter, 15 were deported. Of the 28 individuals, nineteen were of Arabic, Northern African or Persian origin. Unfortunately for the individuals whose cases are pending, the court suspended the ruling for a year to allow for a rewriting of the relevant parts of IRPA. The three most prominent cases — Hassan Almrei, Mohammed Zeki Mahjoub and Mahmoud Jaballah — this means a continuation of detentions that started in 2001, 2000 and 2001, respectively. Pictures: Mohamed Harkat (Algeria) released on bail in June 2006; clockwise from centre left: Hassan Almrei (Syria), Mohammed Mahjoub (Egypt), Mahmoud Jaballah (Egypt) and Adil Charkaoui (Morocco), freed on conditional release in February 2005.

Were those individuals Canadians by birth and — let us put it bluntly — Caucasian and non-Muslim, it is highly unlikely that the public, along with government, would allow their detention to continue for a single additional day without fair trial, let alone a year. But given the current state of affairs in the post-911 world and the racist slant against individuals of Middle Eastern or Persian origin, Almrei, Mahjoub and Jaballah will remain incarcerated without provisions for a fair trial with access to the charges against them. Moreover, the ruling was accompanied by a caveat stating that prolonged detention would be allowed if the new version of the law conforms with the Charter. In other words, despite the seemingly path-breaking ruling, there is no assurance that those three individuals — and others to come — will receive a fair trial, let alone be freed and compensated.

This cannot be allowed in a democracy based on a system of law. Whether they are citizens or not, individuals suspected of participation in terrorism-related activities — this alone casting a wide net encompassing all kinds of activities, both passive and active — deserve the full set of defense tools granted individuals suspected of other crimes. If found guilty in a fair trial, they should face the full consequences of their acts. But we cannot allow for the continuation of a system whereby suspects are detained for years without the means to defend themselves and cannot know the substance of the charges against them — especially when much of the intelligence used to send them to jail in the first place is, as most things intelligence-related, of questionable value, oftentimes based on innuendo, institutional sloppiness, false assumptions or outright racism.

Without provisions for a fair trial and unmitigated respect for the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Security Certificates are only a tool used by authorities to conceal less-than-airtight cases bent on ridding themselves of individuals who happen to be of the wrong ethnic or religious group.

The ruling last week by the Supreme Court of Canada that the antiterrorism provision allowing the authorities to detain indefinitely suspected terrorists was counter to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms — coming less than a month after Maher Arar received an official apology and a $11.5 million compensation from the Canadian government for its role in his deportation to Syria in 2002, where he was tortured — sends an encouraging signal to the world that Canada is in remission and that it recognizes, however belatedly, that some of the things it has done in the name of security have breached its age-old contract with its citizens.

At the heart of the issue are the Security Certificates which, under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), are emitted against foreign nationals or permanent residents suspected of terrorism. The certificates allow for the detention, without a fair judicial process, of those individuals for extended periods of time, pending deportation. Ostensibly to protect intelligence sources (usually foreign) and methods of collection, the accused and their defense lawyers are given no access to the charges against them or the intelligence used to back those charges, making a proper defense in the court of law virtually impossible. It is a system that, not altogether unfairly, has prompted comparisons to the manner in which the US has treated its prisoners in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Eight cases are pending, and twenty have been resolved since 1991. Of the latter, 15 were deported. Of the 28 individuals, nineteen were of Arabic, Northern African or Persian origin. Unfortunately for the individuals whose cases are pending, the court suspended the ruling for a year to allow for a rewriting of the relevant parts of IRPA. The three most prominent cases — Hassan Almrei, Mohammed Zeki Mahjoub and Mahmoud Jaballah — this means a continuation of detentions that started in 2001, 2000 and 2001, respectively. Pictures: Mohamed Harkat (Algeria) released on bail in June 2006; clockwise from centre left: Hassan Almrei (Syria), Mohammed Mahjoub (Egypt), Mahmoud Jaballah (Egypt) and Adil Charkaoui (Morocco), freed on conditional release in February 2005.

Eight cases are pending, and twenty have been resolved since 1991. Of the latter, 15 were deported. Of the 28 individuals, nineteen were of Arabic, Northern African or Persian origin. Unfortunately for the individuals whose cases are pending, the court suspended the ruling for a year to allow for a rewriting of the relevant parts of IRPA. The three most prominent cases — Hassan Almrei, Mohammed Zeki Mahjoub and Mahmoud Jaballah — this means a continuation of detentions that started in 2001, 2000 and 2001, respectively. Pictures: Mohamed Harkat (Algeria) released on bail in June 2006; clockwise from centre left: Hassan Almrei (Syria), Mohammed Mahjoub (Egypt), Mahmoud Jaballah (Egypt) and Adil Charkaoui (Morocco), freed on conditional release in February 2005.Were those individuals Canadians by birth and — let us put it bluntly — Caucasian and non-Muslim, it is highly unlikely that the public, along with government, would allow their detention to continue for a single additional day without fair trial, let alone a year. But given the current state of affairs in the post-911 world and the racist slant against individuals of Middle Eastern or Persian origin, Almrei, Mahjoub and Jaballah will remain incarcerated without provisions for a fair trial with access to the charges against them. Moreover, the ruling was accompanied by a caveat stating that prolonged detention would be allowed if the new version of the law conforms with the Charter. In other words, despite the seemingly path-breaking ruling, there is no assurance that those three individuals — and others to come — will receive a fair trial, let alone be freed and compensated.

This cannot be allowed in a democracy based on a system of law. Whether they are citizens or not, individuals suspected of participation in terrorism-related activities — this alone casting a wide net encompassing all kinds of activities, both passive and active — deserve the full set of defense tools granted individuals suspected of other crimes. If found guilty in a fair trial, they should face the full consequences of their acts. But we cannot allow for the continuation of a system whereby suspects are detained for years without the means to defend themselves and cannot know the substance of the charges against them — especially when much of the intelligence used to send them to jail in the first place is, as most things intelligence-related, of questionable value, oftentimes based on innuendo, institutional sloppiness, false assumptions or outright racism.

Without provisions for a fair trial and unmitigated respect for the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Security Certificates are only a tool used by authorities to conceal less-than-airtight cases bent on ridding themselves of individuals who happen to be of the wrong ethnic or religious group.

Friday, February 23, 2007

The Middle Eastern Arms Race

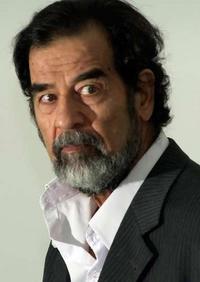

As if the bloody Iraq civil war, continuing flare-ups in Palestine and the occasional bombing in Lebanon were not proof enough of the growing instability in the entire Middle East, the arms trade show that opened last weekend in the United Arab Emirates — and the billions of dollars that mainly Sunni states in the region intend to spend there — surely is a sign that, post toppling of the Saddam Hussein regime in 2003, all is not well in the area.

Of course, for the US arms industry, the news that states like Saudi Arabia, to give but one example, intend to spend as much as US$50 billion at the fare purchasing fighter aircraft, cruise missile and attack helicopters, is delightful. But in the wake of an invasion that was hailed as a new birth for the Middle East (remember the Bush promise of bringing democracy to the region), the arms race by states whose record on democracy is far from envious (again, Saudi Arabia) and whose purchasing of those weapons cannot but prop the undemocratic regimes (if all the projected deals fall through, weapons providers will be making as much as US$60 billion in sales), is as clear a sign if ever there was one that the whole quixotic endeavor was utter failure. Nothing proves this failure more than an arms race pitting Shiite Iran (and its allies in states like Lebanon and Syria) and Sunnis.

Of course, for the US arms industry, the news that states like Saudi Arabia, to give but one example, intend to spend as much as US$50 billion at the fare purchasing fighter aircraft, cruise missile and attack helicopters, is delightful. But in the wake of an invasion that was hailed as a new birth for the Middle East (remember the Bush promise of bringing democracy to the region), the arms race by states whose record on democracy is far from envious (again, Saudi Arabia) and whose purchasing of those weapons cannot but prop the undemocratic regimes (if all the projected deals fall through, weapons providers will be making as much as US$60 billion in sales), is as clear a sign if ever there was one that the whole quixotic endeavor was utter failure. Nothing proves this failure more than an arms race pitting Shiite Iran (and its allies in states like Lebanon and Syria) and Sunnis.

Not satisfied with already having failed in Iraq and perpetuated hatred for Israel through its moral and political support for Jerusalem’s actions in the Occupied Territories and, last summer, in Lebanon, the US is now banking on the fears it has created by demonizing Tehran and its nuclear program — added to its accusations that failure in Iraq is the result of Iranian meddling there — to arm the region.

So, from the prospect of democratization a mere four years ago, what the world now faces is a divided Middle East whose constituents are racing against time to equip themselves with the means to wage war against one another. If, as many fear, the US decides to launch strikes against Iran, either because of its actions in Iraq or, more likely, its nuclear program, Saudi Arabia will have little choice but to side with Washington and could be sucked into the conflict (though, despite the billions it already has spent purchasing arms from the US, the kingdom is far from capable of engaging in a modern military confrontation, as it was in 1991, which led to the deployment of US troops there to prevent an Iraqi invasion; and of course whatever it is that Riyadh bought over the weekend will take years before it is integrated into its armed forces). Furthermore, an attack on Iran cannot but engender some reprisal from Tehran itself as well as its regional ally Hezbollah in Lebanon, which itself is on the brink of an internal armed conflict — a conflict that, in turn, would lead to Syrian and Israeli participation, as happened in the 1980s.

It is surprising how little has changed, except for the amplification, through inept military adventurism and a total abandonment of diplomacy by Washington and, to a lesser extent, London, of old divides. The solution, it appears, is not, despite Condoleezza Rice’s tour of the region, a new diplomatic course, but rather selling an unprecedented quantity of weapons to states on the brink of war.

If, in the wake of London’s decision to pull out of Iraq, Washington still wonders whether it should pack up and leave, a region-wide conflagration involving a mix of terrorism, insurgency and conventional battles surely would be the tipping point. The last time the US took a hands-off approach to a military conflict in the Middle East was in the 1980s, when Iraq launched an invasion of Iran. That conflict lasted eight years, with devastating consequences.

If Taiwan serves as an example (and there is no reason to believe that Washington’s relationship with Middle Eastern states is any different), there is no imagining what the pressure on so-called “allies” in the region for them to buy military equipment must be like. These states are being told that they must buy weapons to a level largely dictated by Washington so that they can defend themselves, or at least hold off until the US can intervene. If they fail to do so, as Taipei now has for a few years, they will be reprimanded by Washington. Through shadowy, backroom diplomacy engineered by influential arms vendors, Middle Eastern kingdoms are spending billions buying weapons that can only lead to their defeat, for no one will ever win such a complex conflict as a Middle East-wide war.

Who in his right mind — except those whose sense of morality has been rotten by greed — could look at the arms expo in the UAE and see this as a positive development? Given the situation, such arms fares should be banned altogether.

As if the bloody Iraq civil war, continuing flare-ups in Palestine and the occasional bombing in Lebanon were not proof enough of the growing instability in the entire Middle East, the arms trade show that opened last weekend in the United Arab Emirates — and the billions of dollars that mainly Sunni states in the region intend to spend there — surely is a sign that, post toppling of the Saddam Hussein regime in 2003, all is not well in the area.

Of course, for the US arms industry, the news that states like Saudi Arabia, to give but one example, intend to spend as much as US$50 billion at the fare purchasing fighter aircraft, cruise missile and attack helicopters, is delightful. But in the wake of an invasion that was hailed as a new birth for the Middle East (remember the Bush promise of bringing democracy to the region), the arms race by states whose record on democracy is far from envious (again, Saudi Arabia) and whose purchasing of those weapons cannot but prop the undemocratic regimes (if all the projected deals fall through, weapons providers will be making as much as US$60 billion in sales), is as clear a sign if ever there was one that the whole quixotic endeavor was utter failure. Nothing proves this failure more than an arms race pitting Shiite Iran (and its allies in states like Lebanon and Syria) and Sunnis.

Of course, for the US arms industry, the news that states like Saudi Arabia, to give but one example, intend to spend as much as US$50 billion at the fare purchasing fighter aircraft, cruise missile and attack helicopters, is delightful. But in the wake of an invasion that was hailed as a new birth for the Middle East (remember the Bush promise of bringing democracy to the region), the arms race by states whose record on democracy is far from envious (again, Saudi Arabia) and whose purchasing of those weapons cannot but prop the undemocratic regimes (if all the projected deals fall through, weapons providers will be making as much as US$60 billion in sales), is as clear a sign if ever there was one that the whole quixotic endeavor was utter failure. Nothing proves this failure more than an arms race pitting Shiite Iran (and its allies in states like Lebanon and Syria) and Sunnis. Not satisfied with already having failed in Iraq and perpetuated hatred for Israel through its moral and political support for Jerusalem’s actions in the Occupied Territories and, last summer, in Lebanon, the US is now banking on the fears it has created by demonizing Tehran and its nuclear program — added to its accusations that failure in Iraq is the result of Iranian meddling there — to arm the region.

So, from the prospect of democratization a mere four years ago, what the world now faces is a divided Middle East whose constituents are racing against time to equip themselves with the means to wage war against one another. If, as many fear, the US decides to launch strikes against Iran, either because of its actions in Iraq or, more likely, its nuclear program, Saudi Arabia will have little choice but to side with Washington and could be sucked into the conflict (though, despite the billions it already has spent purchasing arms from the US, the kingdom is far from capable of engaging in a modern military confrontation, as it was in 1991, which led to the deployment of US troops there to prevent an Iraqi invasion; and of course whatever it is that Riyadh bought over the weekend will take years before it is integrated into its armed forces). Furthermore, an attack on Iran cannot but engender some reprisal from Tehran itself as well as its regional ally Hezbollah in Lebanon, which itself is on the brink of an internal armed conflict — a conflict that, in turn, would lead to Syrian and Israeli participation, as happened in the 1980s.

It is surprising how little has changed, except for the amplification, through inept military adventurism and a total abandonment of diplomacy by Washington and, to a lesser extent, London, of old divides. The solution, it appears, is not, despite Condoleezza Rice’s tour of the region, a new diplomatic course, but rather selling an unprecedented quantity of weapons to states on the brink of war.

If, in the wake of London’s decision to pull out of Iraq, Washington still wonders whether it should pack up and leave, a region-wide conflagration involving a mix of terrorism, insurgency and conventional battles surely would be the tipping point. The last time the US took a hands-off approach to a military conflict in the Middle East was in the 1980s, when Iraq launched an invasion of Iran. That conflict lasted eight years, with devastating consequences.

If Taiwan serves as an example (and there is no reason to believe that Washington’s relationship with Middle Eastern states is any different), there is no imagining what the pressure on so-called “allies” in the region for them to buy military equipment must be like. These states are being told that they must buy weapons to a level largely dictated by Washington so that they can defend themselves, or at least hold off until the US can intervene. If they fail to do so, as Taipei now has for a few years, they will be reprimanded by Washington. Through shadowy, backroom diplomacy engineered by influential arms vendors, Middle Eastern kingdoms are spending billions buying weapons that can only lead to their defeat, for no one will ever win such a complex conflict as a Middle East-wide war.

Who in his right mind — except those whose sense of morality has been rotten by greed — could look at the arms expo in the UAE and see this as a positive development? Given the situation, such arms fares should be banned altogether.

Monday, February 05, 2007

The human comedy

As an editor at a newspaper, many stories come across my desk that seem like they’ve been pulled from a comedy script. Those that I like most are the paradoxes and coincidences that show us that no matter how seriously we humans tend to take ourselves, life tends to have the upper hand and does so with thunderous laughter. Here are three gems that I came across recently.

In late January this year, Taiwan and Israel held their ninth economic and technological cooperation conference. Two-way trade between the two countries for the first 11 months of last year amounted to a little more than US$1 billion. The conference was therefore held to strengthen the links between the two states and encourage further investment and cooperation. There is no small irony in the fact that among the Taiwanese delegation to the conference was the Vice Minister of Economic Affairs, Hsieh Fa-tah (謝發達), whose first name, once Romanized, is oddly reminiscent of a certain Palestinian liberation movement.

The second one occurred yesterday in Grenada, a Caribbean state that in the mid-1990s switched recognition from Taipei to Beijing. For the past years, Beijing has been financing various projects on the cash-strapped island, including a sports stadium whose construction was recently completed. To celebrate the even, a ceremony was held, with the president and various high-ranking Chinese representatives in attendance, including the Chinese ambassador. A band was brought in to play national anthems. The look on Chinese officials’ faces must have been priceless as they struggled to keep their composure upon being served not the Chinese national anthem — but that of Taiwan.

The last one also took place yesterday. During the past week, the Taipei International Book Exhibit was held at the Taipei World Trade Center, close to where I live. This year’s theme was Russian literature, much of which has only begun to be translated into Chinese. In the afternoon, a British man who has made it his mission in the past years to save Japanese forests from the axe by purchasing them held an questions-and-answer session — in Japanese — with the media. Of course, the Taipei Times was there and coverage appeared on page two. Now, another feature of page 2 is the Lunar Prophecy box, which is offered every day and is based on sage advice found in ancient Chinese tomes. The Lunar Prophecy is twofold: it tells people which activities the day is good for and which ones it is bad for. So, as the reader moves his eyes from the story about the man who tried to save forest from being cut toward the Lunar Prophecy box, what does he see under “today is a good day for…”?

Cutting down trees.

As an editor at a newspaper, many stories come across my desk that seem like they’ve been pulled from a comedy script. Those that I like most are the paradoxes and coincidences that show us that no matter how seriously we humans tend to take ourselves, life tends to have the upper hand and does so with thunderous laughter. Here are three gems that I came across recently.

In late January this year, Taiwan and Israel held their ninth economic and technological cooperation conference. Two-way trade between the two countries for the first 11 months of last year amounted to a little more than US$1 billion. The conference was therefore held to strengthen the links between the two states and encourage further investment and cooperation. There is no small irony in the fact that among the Taiwanese delegation to the conference was the Vice Minister of Economic Affairs, Hsieh Fa-tah (謝發達), whose first name, once Romanized, is oddly reminiscent of a certain Palestinian liberation movement.

The second one occurred yesterday in Grenada, a Caribbean state that in the mid-1990s switched recognition from Taipei to Beijing. For the past years, Beijing has been financing various projects on the cash-strapped island, including a sports stadium whose construction was recently completed. To celebrate the even, a ceremony was held, with the president and various high-ranking Chinese representatives in attendance, including the Chinese ambassador. A band was brought in to play national anthems. The look on Chinese officials’ faces must have been priceless as they struggled to keep their composure upon being served not the Chinese national anthem — but that of Taiwan.

The last one also took place yesterday. During the past week, the Taipei International Book Exhibit was held at the Taipei World Trade Center, close to where I live. This year’s theme was Russian literature, much of which has only begun to be translated into Chinese. In the afternoon, a British man who has made it his mission in the past years to save Japanese forests from the axe by purchasing them held an questions-and-answer session — in Japanese — with the media. Of course, the Taipei Times was there and coverage appeared on page two. Now, another feature of page 2 is the Lunar Prophecy box, which is offered every day and is based on sage advice found in ancient Chinese tomes. The Lunar Prophecy is twofold: it tells people which activities the day is good for and which ones it is bad for. So, as the reader moves his eyes from the story about the man who tried to save forest from being cut toward the Lunar Prophecy box, what does he see under “today is a good day for…”?

Cutting down trees.

Friday, February 02, 2007

A reminder from China

Two days before the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was to officially release its much-expected report in Paris on the human impact on the environment and global warming, Taiwan was sent a strong reminder from China that pollution knows no borders, makes no distinction between rich and poor, young and the elderly, and is a threat to all. That reminder came on the back of a cold front coming from China, which with it carried diverse forms of aerosolized industrial chemicals from China’s industrial coastline. Particulate and sulfur dioxide levels were at such levels that the Environment Protection Administration advised people with cardiovascular or respiratory diseases to stay indoors.

Two days before the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was to officially release its much-expected report in Paris on the human impact on the environment and global warming, Taiwan was sent a strong reminder from China that pollution knows no borders, makes no distinction between rich and poor, young and the elderly, and is a threat to all. That reminder came on the back of a cold front coming from China, which with it carried diverse forms of aerosolized industrial chemicals from China’s industrial coastline. Particulate and sulfur dioxide levels were at such levels that the Environment Protection Administration advised people with cardiovascular or respiratory diseases to stay indoors.

Conditions in Taipei City were not as severe as other areas in Taiwan, and yet, when I looked out the window yesterday morning, the effects of that pollution were visible to the naked eye: the apartment where I live is located less than a kilometer from the Taipei 101 building. On any given day, it is perfectly visible. But for a while yesterday the sky had a gray, steel tinge to it and the world’s tallest occupied freestanding structure was hiding behind the veil of atmospheric pollution. Ten in the morning had the light quality of a strange dawn.

Then, as I stepped outside, I fully understood why the EPA had made an advisory targeting people with respiratory or cardiovascular problems: a mere 20-minute walk left fighting for air, and my nose was clogged. All around me, people were sneezing, most of them behind the protective masks so prevalent in East Asia. As there is no alternative to breathing, one has little choice but to take in the foul-smelling oxygen, knowing full well that this implies breathing in some chemicals as well. The most astonishing thing was that a large part of those pollutants, this vaporized industrial waste, had not even originated in Taiwan proper, but in China, more than 100km away across the Taiwan Strait.

The problem of pollution is far worse in China, where environmental regulations are at best nominal only and in most cases inexistent. According to the Guardian, air pollution is responsible for 400,000 premature deaths in China every year. Every year, thousands upon thousands of people die prematurely as a result, and many children are born with respiratory and allergy problems at a prevalence historically unseen. A Chinese government study conducted in 2003 revealed that more than 100 million Chinese lived in cities where the air quality was considered “very dangerous.”

A small reminder after a walk that left me breathless, eyes itchy and nose runny, that whatever the IPCC reveals in its report on Friday, we should take seriously. If the world continues to pollute at the current rate and if its governments continue to see the Kyoto Protocol as a sound bite — if not an object of contempt, as Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper seems to — rather than an obligation to generations present and future, then it can only get worse and other landmarks will begin to disappear, in some areas perhaps for good.

Which brings me to my last point: whether it is true or not that the Harper government played a hand in the sacking of Canadian Environment Commissioner Johanne Gelinas, there is no such thing as being too tireless, or showing too much dedication, in promoting environmental protection.

Two days before the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was to officially release its much-expected report in Paris on the human impact on the environment and global warming, Taiwan was sent a strong reminder from China that pollution knows no borders, makes no distinction between rich and poor, young and the elderly, and is a threat to all. That reminder came on the back of a cold front coming from China, which with it carried diverse forms of aerosolized industrial chemicals from China’s industrial coastline. Particulate and sulfur dioxide levels were at such levels that the Environment Protection Administration advised people with cardiovascular or respiratory diseases to stay indoors.